Why I think Japanese SaaS is undervalued

2025: the year of the digital cliff

Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and is not created to meet your personal financial situation. Nothing should be considered as investment advice or as a guarantee of profit. You are advised to consult with your financial advisors to discuss your investment options and whether it would be a suitable investment for your personal needs. The information used in this publication is from sources that are believed to be reliable but the accuracy cannot be guaranteed. It may include some errors, please make sure to do your due diligence. The opinions expressed are those of the author and the author only. These opinions are subject to change without prior notice.

Disclosure: The author currently owns shares of some of the companies mentioned in the report as of 19 January 2025. The security could be sold at any point in time without prior notice.

Reading time: 43 minutes (…sorry!!)

I want to start with a little thought experiment:

Imagine you just found a time machine and you got curious and decided go back in time. It takes you to Japan 15 years ago. You walk into what would be a typical Japanese corporate office. As you walk around you see filing cabinets that extend from wall to wall, piles of paper and folders stacked up on each desk. In the background, you hear the hum of the paper shredder with an occasional interruption from the obnoxious fax, printing out an invoice from a supplier. What a different world it was back then!

Except you just remembered….

That time machines don’t exist (for now at least), and what you thought was the early 2000s in Japan was just you in 2025. The time machine? Just a fancy-looking box. Why am I making you read this? To give you a feeling of what it’s like to be walking into an average Japanese office today!

So yep, we’re back to our regular programming. You guessed it, I’ll be talking about SaaS (again).

This time it’s not really about a particular stock though. I’ve found myself spending more time looking at SaaS companies I wouldn’t have even bothered looking at 3 years ago as you may have noticed (lol). So what changed? I think Software, especially SaaS is now trading at an attractive valuation - despite what I think is a huge opportunity ahead of us. As it’s inevitably become somewhat of a factor bet for me I thought it would be important to reflect on whether it’s worthwhile to be investing so much in this space. Asian Century Stocks wrote a great Japanese SaaS primer ($) not too long ago. Here I want to add my nuance on this topic based on my experience and hopefully, help others who may be new to Japan familiarize themselves with the local SaaS market which I think is an interesting opportunity set.

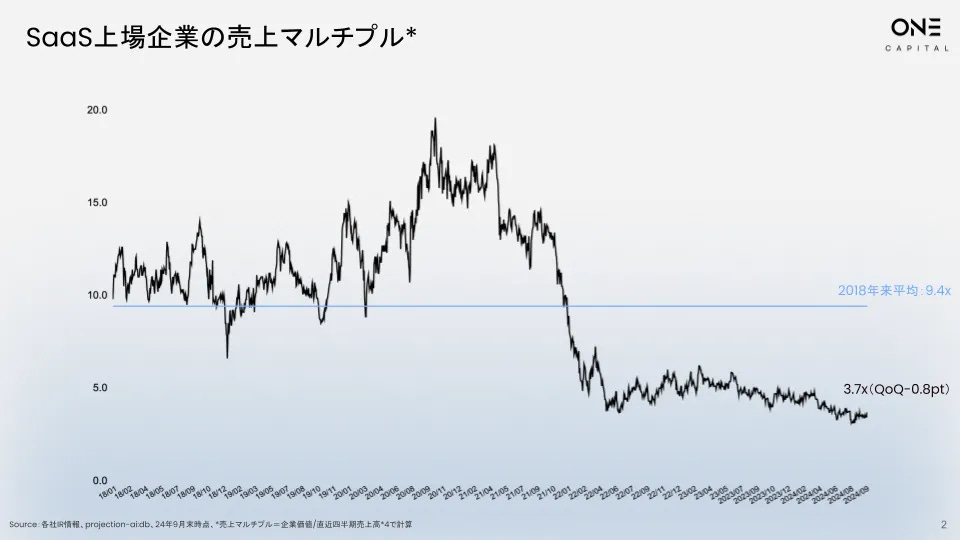

TLDR: with the median SaaS company trading at 3.7x Price/Sales but growing 20%+ and profitable with an operating margin of 15% despite the massive tailwinds in Japan, I believe we can find attractive opportunities in this bucket.

Today I want to go through:

Background of the Japanese Software Industry

Emerging opportunities and catalysts

The state of Japanese SaaS today and why I think it’s undervalued

Other things to consider, including the structural differences and risks

It got way longer than I thought so I do apologize for the lengthy text.

Background of the Japanese Software Industry

Let’s start from the beginning.

It’s been no secret that Japan has not been the most technologically forward society in the world… As a consumer, it was only a few years ago you’d be carrying hard cash to pay for most things as many shops wouldn’t let you pay with your card. If you’re an employee, the chances are that your office is still using a fax in one capacity or another. This seems to be something many investors who have not visited Japan before don’t realize. The joke I used to tell my American friends is “Japan is what the future would’ve looked like 20 years ago” (I have since learned other people have made similar jokes!) Don’t get me wrong, I think we’ve made tremendous progress just in the last couple of years, which I’m very excited about!

If you know how corporate Japan works, you know we’ve pretty much missed the boat on software. For one, some of the solutions are old. It's clunky and the UX still feels like something from the early 2000s. It just….sucks. In terms of sophistication, this has not developed anywhere near global standards. The thing is though, it’s been clear newer solutions can result in massive productivity gains and we knew for yeeeears that we were going to have a labor shortage problem. So the question is - why has adoption been so slow?

In my view, it’s not one particular factor, but a confluence of them. I’ll try to unpack some of it:

Unique IT Ecosystem

Firstly, the IT solutions market in Japan is completely different from the US.

The Podcast Disrupting Japan has a great episode on this which I highly recommend you check out. To put it briefly, the issue can be traced back to the dominance of “Zaibatsus” the original conglomerates. These have since been ‘reformed’ and remain as the Keiretsu’s which is still a significant presence in Japan. Of course, this has more recently gained attention from foreign investors for its complex governance structures. (and partly due to the five trading houses Berkshire invested in of course!). Such dominance has created a market structure where the IT businesses, many of which were part of these groups, have had strong ‘preferred’ customer relationships within their own ‘economic territory’. In essence, these IT companies, known as System Integrators today, only needed to sell tailor-made solutions to such customers without worrying much about competition.

No competition = No innovation.

“Each keiretsu group had their own technology firm who started selling PCs and software, some to consumers, but the big money was in corporate sales. And since the keiretsu liked to keep the business in the family, these technology companies grew and profited by selling to their captive customers within their keiretsu group. And just like before, they made the real money in integration, and customization.

An unfortunate result of this is that the big Systems Integration companies or “SIs” emerged as powerful players, and Japan’s software firms never had to compete globally, or even with each other.”

- Tim Romero, Disrupting Japan

What we see now is that many of these businesses still use what’s effectively tailor-made software. It’s just been that way. Which is great for System Integrators because it can keep customers captive and can charge maintenance contracts ad infinitum. For the user, however, it becomes more and more costly to overhaul the system as time passes. The more stuff they add on, the more difficult it gets. To put it in a bad way it’s ‘easy money’ for System Integrators which also somewhat kills the need for drastic innovation, only incremental stuff. Keeping this in mind we can see this quantitatively too. METI reported that 80% of corporate IT spend in Japan go to maintenance + existing operations. Think about this for a second here - imagine if a larger portion went to newer, more value-accretive solutions. System Integrator dominance has created a unique talent ecosystem where 70%+ of IT engineers end up working them and such vendors with the rest going on the ‘user side’ to become in-house IT personnel. This figure is essentially the reverse of what’s reported in the US. Consequently, expertise has accrued at the IT vendors and not the Japanese businesses (the ‘user’ side), which are now short-staffed on IT personnel and are heavily reliant on these vendors to run their systems.

Unique Business Culture

However, System Integrators shouldn’t be the only ones to blame. I don’t think that’s fair at all. (In fact, I think System Integrators can be fantastic investments as an investor.) It’s important to acknowledge there are some other aspects of Japan’s unique societal and business culture that contributed to this issue. The first is the resistance to change. Japan, for better or for worse, has always thought in terms of stability, really with a focus on minimizing failure over maximizing output. Don’t get me wrong, this is the very strength of Japan as a nation and the root of its manufacturing excellence. In the context of IT, however, the idea of ‘if it ain't broke, don’t fix it’ goes almost against what’s needed in the fast-changing world of IT today. The issue is we’ve managed to do this for close to two decades. Generally, most Japanese corporations that I’ve seen do not like to make the costly decision to ‘rip and replace’ an ERP or critical system which more US enterprises might be willing to do. Too risky, costly, and highly disruptive. So instead what many have chosen to do is to ‘patchwork’ additional solutions on their existing old systems. Again there is a strong bias for this because of the dominance of System Integrators, which have kept customers captive. But it’s now at a point that it’s created such a complex web of solutions that it’s impossible to implement something completely anew. This patchwork though, reduces the risk of affecting everything else and seamlessly fits into the way work has always been done. So it’s no surprise that some of the largest SaaS companies in Japan today are more like ‘single solution’ providers at first, building a solution specifically for one type of workflow. The feasibility and therefore the product market fit simply better suits the unique needs of corporates here. (Note: I’m not talking about verticals, I'm referring to specific functions like invoicing, billing, etc). To make it more difficult, there’s more friction beyond that. The bureaucratic org structure typical in Japanese businesses has meant that decision-making speeds in general have also been slow. Many key decision makers i.e. the CEO and the like, are also older. Inevitably IT literacy among them is lower and are less likely to see the value-add of such new software.

Lack of Risk/venture capital and Entrepreneurship

Furthermore, Japan’s conservative culture means an aversion to any form of risk-taking. This includes career risk i.e. starting a business - which is essential for software development. There’s been a strong disincentive for individuals to take such a high risk. Especially among the younger population (who are more likely to embrace technology), there is a strong deterrence from family and others to do such a careless thing. Many parents of kids that have gone to university the last two decades, would’ve had first-hand experience in watching the bubble burst in the 80s - and this would’ve caused a lasting impression in the way they view things. At least in my experience, your parents can have a strong say in your career, especially as a young graduate. To have a child be a mushoku (無職) meaning unemployed, to start your own business is not only worrisome but even more so potentially embarrassing for the family. It’s also the same when trying to join a start-up, which is also seen as risky - who knows if you still have a job in a few months? These factors have been a not-so-subtle friction in my experience. With the resulting fewer entrepreneurs, I think it becomes one of the reasons why we’ve seen a dearth in venture capital. Also, remember Venture Capital is risk and we don’t like risk! By the way to the government’s credit, Japan has a scheme called ‘Angel Zeisei’ which lets individuals make investments in startups and is basically tax deductible, and it’s existed for years! (Thanks to my friend Matt for educating me on this). So the incentive was there but the interest in such a risky asset class has not been too hot either.

So we have a chicken and egg problem here: Because we didn’t have enough risk takers, VC’s have been limited which in turn has meant it’s been even less safe for any entrepreneur to take any risk at all!! So it’s no surprise that considering all of this we have an incredibly low level of VC investments by global standards. Last reported in 2021 VC investment as % of GDP was just 0.08%.

Source: World Bank: Tokyo Start-up Ecosystem According to JIC, aggregate Venture Capital Investments in 2023 was a little over ¥800bn in Japan. That’s about $5bn USD which is not big in the grand scheme of things. Taking the H1 figure of 2024 it’s on track to be even less at ¥325bn ($2.1bn USD). However, I want to note that the direction of change and the progress made so far is encouraging. We’re seeing a steady increase in VC money. Based on my impression I get the feeling that more recently it’s become ‘cool’ or more acceptable to join a start-up too.

Generally speaking, financial innovation is also more advanced in a country like US, where it resulted in a larger variety of risk capital - which I believe has created tremendous progress for the country. I think this is an underrated component of why America has progressed so much.

Henry Kravis put it aptly when he visited Japan last year. (emphasis my own)

“As credit markets continue to evolve, we believe the Asia-Pacific region presents a particularly compelling opportunity. The region's economic dynamism, rapid urbanization and increasing financial sophistication are driving significant demand for credit across a wide range of sectors. The region is also still primarily dominated by bank capital, accounting for nearly 90% of corporate lending, but it is facing a growing and acute supply and demand imbalance as companies seek more flexible financing and capital solutions. This is particularly true in Japan, where companies have primarily relied on the country's banks for funding. We think that for Japan's economy to be truly resilient, it needs to have access to alternative sources of funding and different types of capital solutions.”

- Henry Kravis on the need for a ‘broad and deep capital market’

(Source: Nikkei Interview - My Personal History)

So I think one of the underrated trends in Japan is such financial innovation is also bound to occur (or say catch up) driven by demand for such risk products. We’re starting to see incredibly interesting local VCs emerge in Japan such as the aforementioned ONE Capital as well as others like Coral Capital. The major US VCs also seem to be entering Japan like A16Z and Lux Capital, really in the last year and a half.

Another welcome change IMO is that we’re more accepting of the idea of ‘failing fast’. At least in my experience, I’ve noticed more and more companies implement and discuss PDCA cycles or Plan-do-check-act in their organization. I think by formalizing failure into a process companies are more willing to accelerate their iteration cycle. Of course, there are plenty of concepts we can draw from the West, but arguably framing failure as a good thing is probably the most important one for Japan if it wants to innovate.

Emerging Opportunities and Catalysts

So why now?

It’s becoming more clear that you can’t simply be using super old systems forever, especially in this fast-changing world, your organization needs agility. I feel we may be at an inflection point. The issue was highlighted by the government as the 2025 Digital Cliff. Something Japanese companies have had in mind for some time now.

According to METI, more than 60% of mission-critical corporate IT systems in use will be older than 20 years! The issue here is that such legacy systems are getting too old and simply not fit to do what they need to do in today’s fast-changing world. The inability to do so is estimated to cost us ¥12 trillion ($77bn USD) annually. What this implies is that we’re going to need a massive upgrade of these systems sooner rather than later and the companies know it. So ok lots of pent-up demand, easy - right? The reality is we’re likely to have severe capacity constraints to conduct such upgrades quickly enough. The reason is because of the 2nd part of the digital cliff, which is that we’re facing a severe shortage of IT personnel already - and that’s about to get a whole lot worse. According to the same paper by METI, it noted that the shortage will expand to ~450,000 Engineers by the year 2030.

What I think is somewhat overlooked in this issue is just how many systems in Japan are still COBOL-based systems (read: hieroglyphics equivalent of programming) so I think a decent portion of current engineers is represented by COBOL engineers. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find good figures for this so it’s just speculation at this point. If true though, we’re facing a more acute shortage of engineers with skillsets that we’ll need for the future. Of course, some engineers have and will re-skill to write in other languages.

One could also argue outsourcing developers abroad, seemingly for ‘cheaper’ in countries like China, India, Philippines, and Vietnam can alleviate the issue. However, I am highly skeptical that companies in Japan would be willing to outsource critical components. What is more likely IMO is that companies would be willing to outsource the non-core part of their development so I don’t think it’s quite enough to alleviate the structural issue of IT talent shortage in Japan.

Related there, is also something called the “2027 Problem” and (if you are wondering we also had (or still have) an unrelated 2024 Problem which I wrote about here… )

The 2027 Problem specifically addresses the issue that SAP 6.0 will reach EOS in 2027. Well technically, free support will end in 2027 and extended support (i.e. not free) is set to end in 2030. You may have guessed by now, many Japanese Enterprises are STILL on SAP 6.0 and the latest version of this was released in 2006! The latest enhancement was in 2016 but that’s still almost 10 years ago!! This shouldn’t be surprising considering the reasons I gave you above. Japanese companies prefer to customize critical systems like their SAP ERP and add on new solutions like patchwork. SAP has already delayed the deadline from 2020 to 2027 so I wouldn’t be surprised if it happened again but the urgency remains.

(As a side note: I touched on this topic briefly with Alpha Purchase $7715.JP for which I think it could become a potential tailwind in the medium to long term.)

Anyhow, this all matters because it means we’re at a crossroads, where we’ll have no choice but to figure out a way to innovate on IT without hitting a wall with an IT talent shortage otherwise we’re f***ed. I believe a part of the answer will be to embrace cloud solutions. There are two vectors here in my opinion. 1) The time has finally come to ‘overhaul’ the old systems. This means that companies will try and look to future-proof their solution to something more scalable and agile to suit this fast-changing world. Cloud is by far the better way to do that especially as companies realize not all solutions have to be completely customized. 2) I’ve mentioned we already have a shortage of IT engineers, such a bottleneck will likely make System Integration services prohibitively expensive to most businesses given the incoming wave of demand versus the available ‘supply’ of IT engineers. Naturally, scalable cloud solutions like SaaS - where the incremental cost to reproduce a solution is minimal - can be one part of the answer to reducing this bottleneck. Recalling that still a major chunk of IT spend is on maintenance, at this juncture, this could be re-directed to new solutions going forward.

Surprisingly, although still low in penetration compared to RoW, SMBs in Japan have been more receptive to SaaS/cloud earlier than Enterprise it feels. Note that Japanese SaaS majors have generally scaled through SMBs rather than enterprises. I guess this makes sense given the labor shortage that SMB’s suffer is more severe than the large corporations. If you ask anyone in Japan who’s tried to sell SaaS using a Public Cloud to an enterprise 5 years ago, they can tell you how reluctant many of these companies were, citing concerns about the ‘security risk’ of Public Cloud and the difficulty of migration. (Atled for example rolled out a cloud product for SMBs first, and only recently did the same for Enterprise) On the other hand, you will be surprised just how much that attitude has changed in the last 4 years, with enterprises now starting to embrace the public cloud.

I think we’re still very early, and the value of IT may still be overlooked by many of these firms. A funny episode from last year was the Cyber attack at Kadokawa $9468.JP which is an entertainment company and a major owner of Anime IP. They were a victim of a ransomware attack and were reported to pay $3 million USD to hackers. The peculiar part of this debacle was that Kadokawa since sought to strengthen their cyber security and put out a job listing for a security engineer for ….. an ¥8mn annual salary which is an equivalent of 50,000 US Dollars! Is this really the insurance you’re going to want to pay for potentially larger and more costlier hacks in the future? DreamArts recently published a report based on their own survey that 68% of management personnel at Enterprise companies feel they have sufficient security measures, and another 24% responded ‘mostly sufficient, but with some room for improvement’. This is a dangerously high level of confidence considering the survey also found more than 63% of respondents also admitted there was some kind of security incident in the last year! Ignorance is bliss but in this case not, and goes to show there is a lot more progress to be had in terms of IT literacy and education among key decision-makers.

Anyhow, 2025 is an arbitrarily designated turning point and arguably DX adoption has accelerated ALOT since Covid, when employees working from home realized that it’s completely unfeasible to do any kind of work if they’re dependent on paper (i.e. having to go into the office to get stuff signed). I illustrated a hypothetical example in my Atled Article.

Say that you have a purchase agreement you received from your supplier. To go forward you usually need to get approval from your manager. Easy peasy. However, maybe this particular purchase agreement is for a transaction worth more than ¥100 million, and for that instead of just getting approval from your manager, he needs to ask his manager - who’s on vacation and who might in turn, need approval from compliance. Compliance then might have a question on the terms of the purchases which might take another few days to review. But wait, given this purchase agreement is related to IT-related purchases, it only needs to be signed off by the CTO! By this point, you’ve already wasted a couple of days waiting for the others to get back to you.

I didn’t add in the original article, but the contract would’ve needed to be signed off by your CTO physically. This painful experience where many companies were given no choice but to adopt these solutions has made many realize the value of modernizing the existing IT infrastructure. The government also set up a Digital Agency dedicated to improving digital adoption in government (and indirectly the private sector) through DX. The term “DX” short for digital transformation is now a term widely used by businesses in Japan.

Thus in general, we’ve seen a supportive environment from a regulatory standpoint. Examples include the aim to shift 100% to Electronic Health Records in hospitals by 2030 and the integration of My Number Card (something like a social security number) with digital solutions in healthcare. In April 2023 it became mandatory to have online verification systems to check the eligibility of healthcare coverage in medical institutions.

Furthermore, the Japanese government is well aware of our digital deficit (You can find more details with the excellent piece written by my friend East Asia Stocks here). To me, it seems like a reasonable bet that the government will try to keep pushing to reduce such a deficit though it may not completely be able to close it. This means that there’s every incentive to introduce more subsidies and supportive regulatory changes in the future beyond what’s already present. In other words a tailwind for domestic software companies.

Hopefully, in the future, we’ll look back at Covid and the ensuing years as the catalyst that lit the DX tinderbox.

The State of Japanese SaaS today and why I think it’s undervalued

Overall whilst I believe software in general feels pretty undervalued in Japan, I’ll stick to just SaaS for the purpose of this discussion. I’m grateful for One Capital as a source here and for creating the ONE Capital Cloud Index similar to what Bessemer created with the BVP Cloud Index. It’s been helpful to try and quantify my current views.

Why it’s cheap

There’s a few reasons why it’s gotten cheap. First and foremost, I think growth has been out of favor for the last couple years and SaaS would’ve been part of this. There are 2 ways I think about this.

a) the recent strength in Japanese equities has mainly been in ‘value’ stocks namely those that are improving governance and shareholder returns/capital allocation/ROIC → a typical area where activism is employed. Arguably these scalable SaaS businesses already have excellent ROIC/ROCE profiles and are more shareholder-conscious in general so it doesn’t quite fit the mold of what’s sought after today. There’s been strong institutional interest in Japan but since many of these SaaS companies are too small they’ve not really benefitted from it. Some large caps have done well and what’s more likely is there’s even less interest today as the only real investors that can own them, namely retail, have also moved to large caps to chase performance.

b) The SaaS companies were ‘guilty’ of fetching astronomical valuations during the Covid hype which consequently never lived up to what was expected of them and got sold off. Understandably global risk-free rates ‘normalized’ and long-duration assets such as this likely got sold down. Given the small size of many of these today, it’s likely that some of them have fallen into what I like to call the ‘micro-cap death trap’. The stock gets sold off → market cap gets too small for sophisticated funds to invest → so they sell off more → liquidity deteriorates → only investors holding are retail investors and stock is left for dead. The illiquidity discount is real. However, this also offers smaller investors to enter before the institutions do.

The other potential risk I suppose is the rapid rise of Artificial Intelligence in the last 2 years and the perceived fear of that potentially bringing the value of software to zero. (I’ll share my thoughts in the ‘other considerations and risk’ section)

Market Opportunity Size

Now using the index constituents let’s try and put things into context.

The total market cap of these constituents is ¥2.2trn in USD that’s… $14bn USD!

The cumulative sales of the constituents is ¥488bn which is just $3bn USD! Now to put it into context let’s compare it to a System Integrator Major, NTT Data $9613.JP, the domestic revenue from this one company alone is ¥1.8trn (just shy of $12bn USD) which is larger than the sales of all listed SaaS companies combined. Do we really think this industry will mature any time soon? NTT also conveniently defines its market size, comprised of IT services to Public/Social Infrastructure + Finance + Enterprise to be worth ¥19.3 trn just with these 3 end markets alone. As a sanity check, METI reported in 2020 that Software/IT services were worth ¥25trn so it doesn’t seem too crazy (2020 was pre-Japan’s DX everything phase) Anyhow public SaaS represents only a tiny fraction of this.

Fundamentally while some of these are niche solutions, I think many of them still have a massive opportunity. Many will surely inflate their Total Addressable Market (TAM) on their IR pres but even when you put some kind of discount to it, I’ve found many to still have considerable room to expand. So the opportunities for these companies remain pretty big.

On the whole, we see that the median Sales growth has sustained above 20% yoy and more importantly, these companies have done a fantastic job expanding margins over the last 3 years or so, demonstrating that it’s profitable without promising margins 5-10 years in the future whilst growing at decent rates. Note that the median SaaS company almost reaches a ‘rule of 40’.

The valuation maths:

Based on the One Capital Cloud Index, as of Q3 the median Market Cap/Sales, effectively Price/Sales was 3.7x and the operating profit was 15%, the median growth has been above >20%. On a quarterly basis the median ‘rule of 40’ calculation has oscillated between 33%-38%ish.

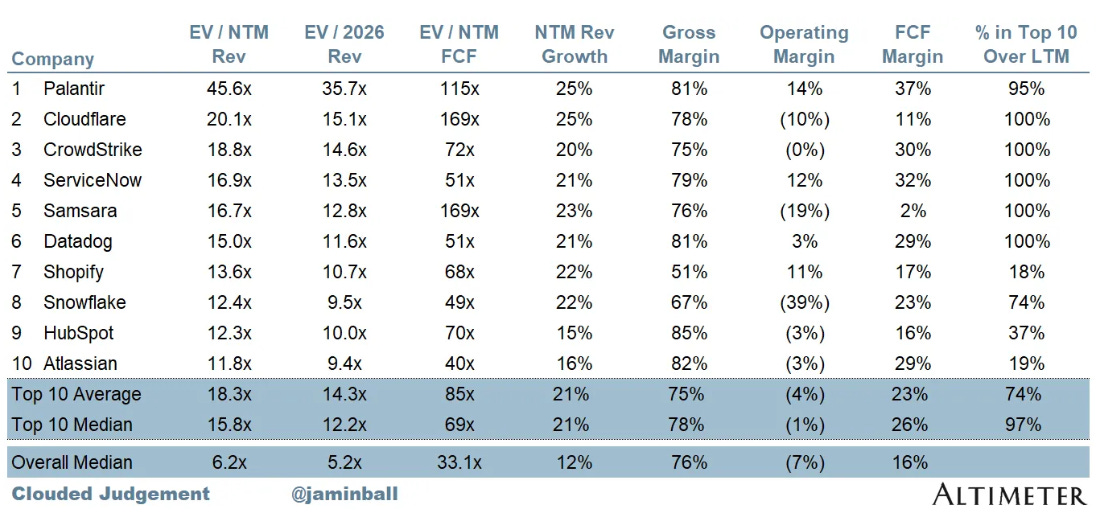

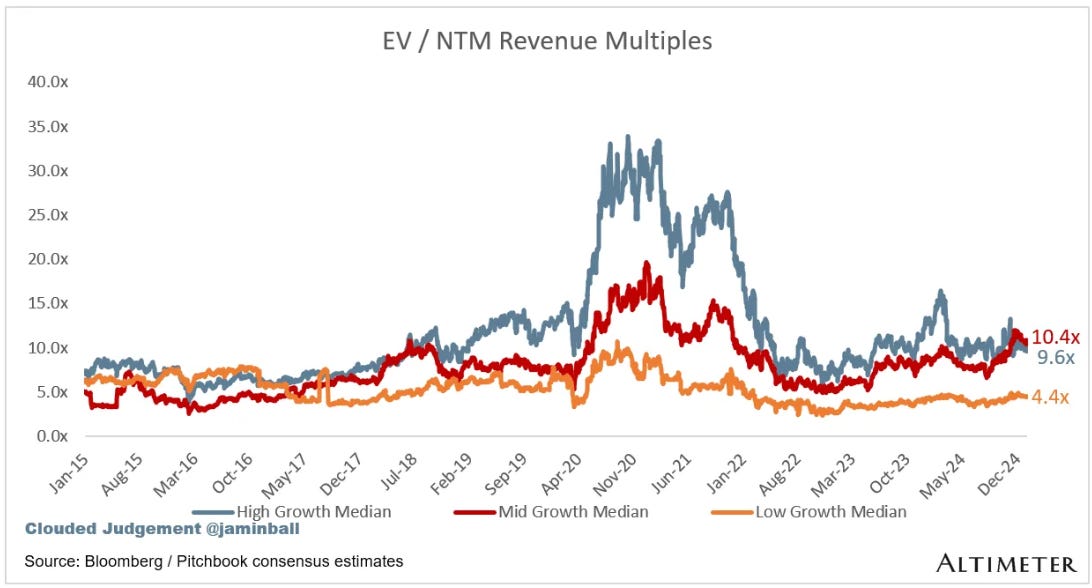

This is interesting when you compare it to the US SaaS data provided on Clouded Judgement by Jamin Ball and Altimeter. The median NTM revenue growth is 12% overall while the median operating margin is negative 7%, all the while trading at an NTM EV/Sales of 6.2x! Meaning it’s trading at a 70% premium despite the worse metrics. Also, remember the One Capital Cloud Index uses Market Cap and not Enterprise Value so the gap is potentially larger. Many of these Japanese SaaS companies are cash-rich.

If you take the top 10 EV/sales companies in this cohort the median revenue growth is roughly in line with the Japan SaaS index at 21% whilst the median operating margin is still -1% so fundamentally speaking this also looks worse but the median trades at 15.8x NTM EV/Sales. At least statistically Japanese SaaS looks much cheaper. They also report the median EV/Sales for 15%-27% topline growers trade at a valuation of 10.4x. The US is home to some of the best companies in the world so surely there’s a premium for that + the market seems to be ‘overheated’ but this still feels like a massive delta to how things are being valued in Japan.

Notice that based on the One Capital Cloud index, it trades below pre-COVID levels as well. Which I’m not sure is fair given the potential TAM and the increased willingness to adopt such solutions by Japanese corporates. I concede that the index has added more companies over the years since many have also listed in the last 3 years which likely causes some distortion.

Not the biggest fan of doing this type of math on an entire cohort as it can be prone to errors but just for the sake of another perspective let’s assume that the Japanese SaaS cohort is a single company and try to look 3 years out. So it’s currently trading for 3.7x Price/Sales with a 15% operating margin. For the next 3 years let’s also assume the below:

Sales grow at a 15% CAGR over 3 years: assume growth matures and gradually slows from 20% today. (Unlikely and conservative, if the TAM is truly as big as I think it is)

Reaches a ‘mature’ margin with a 30% operating margin: Many mature software companies and/or product segments in Japan easily do 40-50%+ margins at maturity so I don’t think this is outlandish. The median gross margin today is also already 70% so feels doable.

No debt: most SaaS companies are highly cash-generative so no debt is needed. Also conservative as this assumes no further cash accumulation and they also tend to be cash-rich already.

Dilution is not big (generally stock options are not as widely adopted and aren’t as attractive an incentive because you get taxed like crazy)

Based on this we can extrapolate the forward 2028 Price/Sales will be 2.4x and the implied Price/EBIT will be 8x. Cost items are pretty simple so no complicated adjustment is needed. Apply a 30% corporate tax rate and we arrive at what’s effectively a P/E of 11.5x. Note that I don’t adjust for/assume any shareholder returns or cash accumulation. Is this implied valuation really what Japanese SaaS has left to show? I’ve laid out how large the runway potentially could be, and it feels to me otherwise. This would also imply it will also trade below the average company in Japan. I’m not sure this is fair even if growth actually matures in 3 years given the predictability, scalability, and cash-generative nature of software. Even if we assume 20% ‘mature margins’ it still looks cheap. Many TOPIX constituents still have a large exposure to cyclical end markets that SaaS usually doesn’t. I’d also say that many of these SaaS companies are run by younger management that’s generally more shareholder-conscious, so the chances shareholders will gain from capital returns are also good.

I also think competition in this market is less intense relatively speaking than in the RoW because it’s still so underdeveloped. This is interesting to me. Because there are some incredible founders among this cohort of companies that have already developed a competitively advantaged business. In some cases, I think it’s become almost impossible to replicate. Barring a few areas, we see that many domestic players aren’t competing with any foreign software companies at all. In fact, for many, its main competitor still tends to be either paper or Excel.

Japanese software is potentially in an enviable position because of the structural barriers for foreign players that have deterred them from entering thus far. The unique differences in: needs among Japanese Corporates; GTM strategy; labor-intensive sales; lack of brand awareness have meant there’s been limited success by foreign software bizes to gain meaningful presence as a whole. (“Constellation Software? Who the hell is that?”) The only noticeable ones IMO has been generally the majors i.e. the Public Clouds, Microsoft, SAP, SalesForce, and a handful of others. There are also uniquely Japanese pain points that Japanese SaaS companies try to solve which foreign companies simply don’t have an answer for. SanSan for example initially started with their solution to read information from a physical business card onto a company’s digital database. If this sounds odd, in Japan we don’t do LinkedIn, we generally still exchange physical business cards (surprise!). Unique market structures in certain verticals like for CYND for instance, will also mean that there is literally 0 incentive for global companies to adapt as the market opportunity may not be large enough at their scale to make such costly adaptations. Needless to say, Japan is a HUGE market with meaningful white space left, even if some global majors do succeed, I think there will be plenty of space left for local players to shine.

Interestingly, SaaS as a category has remained a popular sector for Japanese VCs being the second largest category for investment as of 2024H1 after AI. A notable private SaaS company SmartHR raised $140mn USD Series E in 2024 with an implied valuation of $1.6bn USD. The latest ARR reported in Feb 2024 was $100mn USD (+50% yoy) so the rough valuation is around 16x ARR. Private market valuations usually lag public ones, but it’s been a few years since things got ugly. So to me, it looks like VCs are more excited about SaaS than the public markets even today.

Other considerations and risks

Before we get too excited, I think it’s also important to keep in mind the potential structural difference to the rest of the world and the risks to this thesis. This is definitely not an exhaustive list but some I believe are worth highlighting.

Foreign Exchange (FX).

This one I find is quite an under-discussed component of Japanese SaaS. The largest provider of public cloud infrastructure in Japan is no different to the US. It’s Amazon Web Services (AWS) by Amazon and Azure by Microsoft. What is interesting here is that the bill Japanese SaaS companies pay to these providers is denominated in US Dollars. This is important to understand because, for a typical SaaS company, hosting costs are a decently sized component of its cost base - maybe after marketing + personnel costs allocated to development and sales. So one way we can look at the cohort of SaaS companies is that they’ve been able to improve profitability in the last few years despite the significant weakening of the Yen versus the US dollar. So far I am not aware of any SaaS company that does any kind of extensive forex hedging to offset this. This of course is a double-edged sword. Should the Yen strengthen this could be accretive to margins. On the other hand, if the yen continues to weaken, as many seem to believe, this would add pressure to the margin profile.

One ‘test’ and upside to the current SaaS valuations is that we’re starting to see some solutions raise prices. Although some do a ‘stealth’ price increase which is really by selling additional features. There are now some that do it outright, and so far quite successfully. This can potentially offset some of the margin issues that may be caused by external factors such as FX and increases in wages which I’ll talk about next.

Labor laws

In general, Japan is an interesting market to invest in because certain industries are less developed compared to other nations. You can look at similar industries abroad to extrapolate key insights to apply to Japan. I am a believer in learning from best-in-class examples around the world to build a strategy and apply what worked. In my mind, the US is by far the best market to look at for insights on SaaS. However, one point I feel is somewhat misguided is the adoption of the US go-to-market strategy for SaaS. This I define as investing heavily in growth and worrying about margins later. This seemed especially pronounced around 2021 when the typical pitch for a US SaaS was something like “We’ll grow fast at XXX% and our long-term run-off margin will be 40% in 5 years”. Of course, some didn’t in the end but not the point here. Some listed Japanese SaaS companies also looked to employ that model, and at times because US investors would encourage them to do so. My main problem with this though is labor laws. I’ve mentioned earlier but we’ll continue to have a strong reliance on domestic Japanese-speaking engineers for some time - the issue is that in Japan we have highly protective labor laws meaning that it’s extremely difficult to fire someone or conduct large restructurings. Even if you did manage to fire people, you will have a reputation for that and it’s going to be difficult for you to hire people in the future (in a market where there is already a labor shortage).

So, if you pursue ‘growth first, margins later’ and don’t get your long-term unit economics right in Japan you are screwed. You’re bound to make an error if you’re trying to look 5+ years out, the future is hard to predict. For instance, how much of the wage increases we’re seeing today do you think many of these businesses modelled 5 years ago? Inflation seemed inconceivable back then. Even with a solid LTV/CAC projection, it can still go awry. My point here is that in the US, it’s much easier to cut down on people than it is in Japan due to both legal and cultural reasons. So the worst case re-allocation of labor can occur much more fluidly in the US - offsetting mistakes.

Compound the strict labor laws with the problem of overestimating your unit economics and you’ll find that your business might be structurally unprofitable. So maybe I’m conservative, but I think in Japan the model to grow more steadily while keeping a certain level of profitability is the sound way to do things given the external circumstances specific to Japan. In any case for a public company and they seem to be doing just that. Should these companies still find ways to grow faster while spending less money? Absolutely. I look at a company like Rakus $3923.JP, which has never really been loss-making whilst being able to sustain a high growth rate.

A Japan-only solution/Cultural barriers to entry

Because of the relative immaturity of the Japanese Software Industry in terms of sophistication, the TAM it can address will likely be smaller than that of its US counterparts - which have shown their incredible ability to go global. Whilst the solutions in Japan are good for Japanese customers who have a unique need, the flipside is that most will lack competitiveness abroad as this is not so much a globally standardized solution. So here is another double-edged sword, on one hand, the unique ecosystem in Japan may prevent outsiders, even large ones, from entering the market but on the other hand, many Japanese SaaS companies will likely be inadequate to expand abroad due to the high competition and lack of understanding and capability to serve the global markets. There are countless tales of Japanese software businesses that’s tried to do something in the US (look at how much money is being burnt by Cybozu to sell Kintone in the US). This means the market cap of such a company will almost never reach the scale you’d expect for a large US SaaS.

As you also saw, Altimeter’s index I compared to also has more enterprise solutions which IMO should be valued higher. So there’s likely some skew in valuation caused by this as well. Having said that, some of these in Japan are enterprise solutions, and still trade below that!

System Integrator Dominance will continue

I have no doubt in my mind that System Integrators, the core and gatekeeper of Japan’s IT systems will continue to be a meaningful presence in Japan. They’ll still continue to manage customer lock-ins with newly developed systems and they’ll continue to build/capitalize on the close relationships they’ve already built with customers. This means they’ll also build their own in-house SaaS solutions that can be rolled out to their customer base. Besides, SaaS companies also rely on them for distribution. So this is also a caveat you have to keep in mind with the TAM maths I did before. The One Capital Cloud index does not capture the larger System Integrators and Packaged Software companies that are transitioning to their own SaaS products which I like to call hidden SaaS. So current SaaS TAM is likely higher than what you may think. That said, based on my personal experience (or if you currently work at a Japanese firm) we have a long way to get rid of paper.

Not all companies will necessarily move to the cloud either. I’m already reading reports on companies that are now having to replace the ERP system they’ve used for 30 (!) years. The issue is that for such a company, next-gen ERP migration is something that could be unfeasible based on it’s own unique existing architecture. Instead, they will directly migrate their COBOL apps to a ‘newer environment’…

Illiquidity

Unfortunately, because of the small size I mentioned earlier, there is also a liquidity issue for the stock to garner any meaningful interest for now. So it’s prudent to take that into account as to why the stock is cheap today. That by no means is a bad thing IMO. If you get it right and the earnings scale enough to a place where it justifies a higher market cap, you could potentially enjoy a significant re-rating in the stock as this liquidity discount dissipates. In addition to that once it crosses the ‘chasm’ which I define as the company entering the institution’s investible universe it can become rocket fuel to drive a further re-rating.

Interest rates

Whether you like it or not this type of growth i.e. long-duration assets are going to be swayed by the cost of capital more. Especially in Japan where there are blatantly cheap companies based on asset value i.e. based on the value today. Why the hell would you need to be betting on some earnings projections of the future? This is a fair argument because, on a risk-adjusted basis, asset-based investing may be much more attractive. Ultimately we’re not just thinking about what makes a good business but what makes a good stock, and the whims of the interest rate (specifically the US treasury rate) could have an outsized impact on growth companies in Japan. Regardless of whether it’s cheaper than US peers, it’s more so to say that this kind of factor can and will move certain categories of stocks. In addition to that, SaaS/Growth may be out of favor for longer than we hope! 2025 is the earmarked ‘turning point’ but who knows!

The AI Agent Era

The elephant in the room of course is AI. There’s been a lot of conversations about the dawn of AI and the highly disruptive nature of it. Maybe this is also priced in to some extent. Much like many others, I also believe that AI will be the future of humanity to build a super-human society. It truly feels like magic sometimes. AI will absolutely be beneficial for Japan and can be a deflationary factor for rising IT engineering costs.

I don’t want to dismiss this risk and will certainly be weary of it. I generally think humans are not made to think exponentially but linearly. To that end, we’re bound to underestimate the exponential nature of AI despite knowing just how powerful it can be. (Quite frankly, I think we still continue to underestimate the internet, another exponential growth concept, today!!!). Even if you think this might be a 100x opportunity, the chances are you’ll have to add a couple more zeros to it.

Again, it’s hard to underwrite this risk with any real accuracy but there seems to be a belief that AI will obliterate software. Usually, the conversation goes something like:

Investors: “How will AI disrupt your business”

Software Company: “AI will be beneficial for us”

Investors: “Yeah that’s what they all say”

Right now I’m leaning towards the idea that AI will be beneficial for software. For me, there are several questions I’m wrestling with. Assuming AI gets to a level enough to build competitive solutions - Like, who’s going to sell the AI Agents here? Are SMBs (a majority of bizes in Japan) really going to proactively seek and buy solutions? These are the same bizes that needed people to come into their office to explain and sell software to them (not even an online video call sufficed).

“Poor sales rather than bad product is the most common cause of failure. If you can get just one distribution channel to work, you have a great business.” - Peter Thiel

Once they implement AI, how will these businesses make sure it’s compatible with their complex workflow which mixes physical world processes and digital ones + other customers/business partners? How does this all tie in from a regulatory perspective? This question becomes even harder to answer with Enterprise. For new entrants that look to ‘disrupt’ existing systems using AI - what’s the USP here? That they’re using AI so they can set a lower price? I’m of the opinion that incumbents will have way more resources to deploy AI effectively and create more value through any resulting efficiency gains. I do think that AI can commoditize certain applications but the total takeover of AI seems unlikely, and what’s more likely is that the Software companies and System Integrators will be the gatekeepers for AI deployment. They can use it to 1) enhance the existing product suite and 2) reduce their operating costs significantly by automating their internal processes. So I find it unlikely that these companies will churn because of AI. If a product is low-churn today, there’s a good reason for that. (and remember some of them don’t even want to switch from COBOL LOL!)

(This one I’m really not sure so will leave it as an open question but to what extent can we justify compute costs for using AI versus current software modules for certain tasks? Or does that not matter because you’ll need fewer engineers as a result? )

There is an interesting company called FastAccounting ($5588.JP) which deploys AI for accounting workflows in Japan. Seems like a great biz and I’ll be following to see how it all develops! Note that for the time being it seems like even they are working closely with other ERP and workflow solutions.

Risk is still risk, and I do think it’s still important to try and find the areas where you’re least likely to encounter such disruption. So while I think SaaS is cheap as a whole, some are definitely more attractive than others. For Japan as a society, I’m incredibly excited about the potential implications of AI adoption. For one, if it can write code, that’ll definitely offset some of the IT talent shortage we suffer from. In many ways, it could also help alleviate our labor shortage.

“In my personal view, Japan missed software. I think a lot of that has to do with the user interface in the kind of special characteristics of Japan, where the interface is built to only work in Japan for almost every product. But now we're entering a new era, we're no longer going to use Windows, icons, etc. It's going to be natural language, which gives Japan a whole another shot at software.”

Ben Horowitz

Conclusion

So my conclusion here is that it’s probably no coincidence that I’ve been writing so much on SaaS the past year. The SaaS field in Japan feels like an interesting opportunity to look for ideas today. The business model is attractive with high margin, high growth, and strong cash generation yet, looking out a few years it trades as if we’ll hit maturity already which I don’t agree with. Many are also pretty cash-rich! I don’t think we’ve really ‘missed the boat’ by any measure and we’re underestimating how much more room there is to grow. It is still early but conversely, competition will likely increase over time as the industry grows - so picking your spot will continue to be extremely important. However, by finding a handful of ideas across different verticals/applications, this could be a good way to ‘diversify’ your risk.

As a foreign investor, you may be somewhat reluctant to look into these companies because you don’t understand the local market. To that, I say don’t be! One significant advantage you have over local investors is that you have an incredible resource/knowledge library namely all the major SaaS companies that exist in the English-speaking world. This not only applies to software but there are certain industries abroad that are simply more developed and mature versus the equivalent in Japan. Through this you can figure out: potentially relevant market risks, a better idea on long-term unit economics, product competitiveness, etc. My friend calls this the ‘time machine principle’. I would not underestimate this advantage. Yes, you have to consider certain structural differences but I will go so far as to say many Japanese Investors won’t know such peers exist. I realized not even many well-established domestic sell-side analysts do, who seem completely siloed. In other words, Japanese investors have the advantage through local market insight, but you can look at these companies from a completely different lens which could lead you to a differentiated insight.

Though not SaaS, I’ll end with a real story with a parable:

A Japanese friend, who is just an incredible investor (and person!) has some family in Europe and had to open a bank account there. This was his first exposure to ‘digital banking’ for him which is something that was still pretty foreign in Japan. According to him he was shocked at how convenient and easy it was, with minimal paperwork. It immediately struck him with the value that this brings and how Japan can benefit from this in the future. Soon after, he invested in a company based on that insight he brought back. That company was called SBI Sumishin Net Bank $7163.JP and it’s probably up more than 150% since he invested.

Epilogue

If you want more tangible insight on SaaS businesses, I’ve written about several in the past which I’ll list below for your convenience - some of which I think are still attractive today.

Alpha Purchase ($) - (not SaaS but since I mentioned it :))

If you haven’t yet Will’s Japan Business Insights also has a trove of interesting information on Japanese Software that I recommend you check out!

In part two I may add further reflections (I usually get ideas and spot mistakes as soon as I hit the send button) but I’ll mainly focus on doing a short profile of several Japanese SaaS companies I’ve found interesting.

I’ll end it here for now, hope this helped you understand the Galapagos that is Japan (even a tiny bit!) If you enjoyed it, I’d appreciate it if you could share it with your friends :)

Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and is not created to meet your personal financial situation. Nothing should be considered as investment advice or as a guarantee of profit. You are advised to consult with your financial advisors to discuss your investment options and whether it would be a suitable investment for your personal needs. The information used in this publication is from sources that are believed to be reliable but the accuracy cannot be guaranteed. It may include some errors, please make sure to do your due diligence. The opinions expressed are those of the author and the author only. These opinions are subject to change without prior notice.

Disclosure: The author currently owns shares of some of the companies mentioned in the report as of 19 January 2025. The security could be sold at any point in time without prior notice.