Book Summary Part 2: "Our Investing Strategy, who does the market smile upon"

Or... "How to be down -72% but 93x your fund anyway"

Yep, part 2 is finally done! If you’re curious about what the hell I’m talking about, go here for part 1 :). Instead of just a simple summary this time, I researched Mr. Tatsuro Kiyohara’s past trades to see if I could dig up anything interesting. (I have some fun bonus content). There’s a lot in the book itself so I’ve picked out what I felt were the most interesting parts for me. I would definitely still buy it if and when an English copy comes out.

I'm happy to have had some time between part 1 and part 2 since it forced me to re-read the book. It's always amazing to catch the nuances you might have missed the first time. What I enjoyed is that through his trades, you can also see the quirks of the Japanese equity market, which to many of you is probably useful.

Unlike part 1, I’ll try and stick to chronological order to help you try and understand just how difficult and unlikely his 25-year run was. I don’t think anyone would’ve honestly survived.

Reflecting on it, it's one of the more raw accounts of an investor that I've come across. Munger's quote "Show me the incentive and I'll show you the outcome" perfectly describes it. I mean, what was his commercial incentive to write this book? It's clearly not to raise funds or make money. Other than the fact that he wanted to share his story, leave a legacy and teach aspiring investors how to do it I couldn't think of much. The lack of incentive to keep clients now that he's closed his fund meant we got to see some dead honest thoughts on why he did what he did. To me that's valuable. As a man who thinks deeply about probability, he'd probably appreciate me saying that the account of his adventures also reminds us of the sobering role of luck and not just skill alone. Not that he was lucky (you can't do it for 25 years otherwise) but there were pivotal moments where the outcome of survival was out of his control and there was no way just sheer intelligence could've gotten you out of it. That said he did take insanely brave steps to improve the odds. At the end of the day, this book exists not only because he was intelligent but because he survived, and he most definitely deserves praise for that. As Franz Beckenbauer said, "The strong one doesn't win, the one that wins is strong."

Like last time, italics = my thoughts and reflections. And also If you think I've missed something or mistranslated let me know! (This piece is long, so I'm bound to)

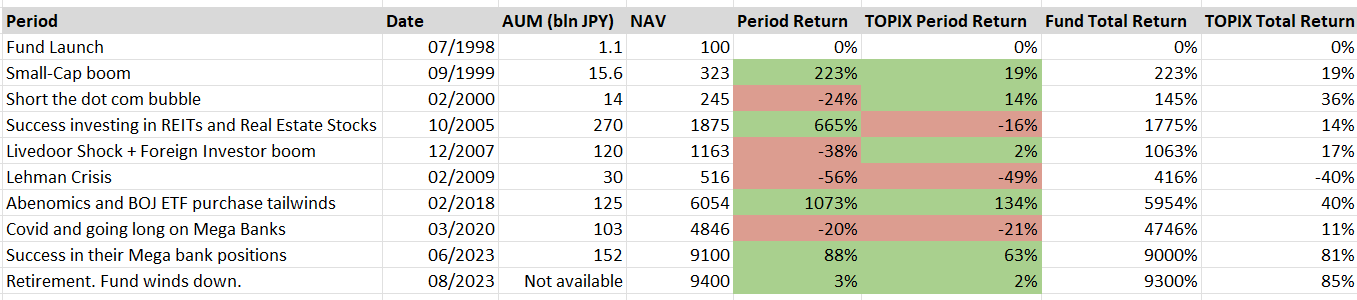

Just as a reminder the ‘phases’ of his fund

I couldn’t find his yearly returns so based this on whats mentioned in the book. I’m just using the last day of the month for each data point so some inaccuracies.

I couldn’t find exactly when his fund closed, which only mentions Summer 2023 so I guessed the end of August.

Topix returns are based on a simple price return.

July 1998- Sept 1999: Fund launch, small caps take off

The fund marketed its strategy as "doing the opposite of giant institutional investors". In other words, the core strategy was to be long small/micro caps (which no institution touched) and short large caps.

Even as the fund scaled over time, micro/small caps continued to be a core part of the long book. Short positions were focused on over-priced large caps.

recently asked on X how diversified Kiyohara-san’s portfolio was and it's a good question. It was hard to confirm his portfolio composition with a lack of information online. I think he had a bias for concentration since he even explained this with probability theory. I get the impression that given his focus on smaller companies on the long side, the fund moved increasingly to a more diversified long portfolio as it scaled. I got this from the fact he mentions the impossibility of investing in a concentrated manner into these stocks at a large scale (the market impact is too large) and that the fund was already at its optimal size for this strategy just a year after launch. It would be common for him to take a year to build a full position in some of these stocks. Near the end of his run, he returned to concentration with a large portion of his portfolio in mega banks. His short book did exactly the opposite, his shorts evolved to a more concentrated strategy over time (more on that later).I would add that he did invest in large-caps when the opportunity warranted but it was more event-driven and followed a different process to investing in smaller companies. At the extreme, he'd invested in these companies after only 1 hour of research without having followed the name beforehand.

But at least initially, he was concentrated on his longs alright...

One of the first trades he made was Nitori.

Right before launching his fund, Hokkaido Takushoku Bank went bankrupt and was undergoing liquidation. He immediately decided to use that opportunity. He went to Sapporo to buy the shares of a specific company from them, which was Nitori a company with almost zero liquidity at the time. Some readers may recognize the name today as the largest furniture retail chain in Japan oft compared to Ikea. They’re known for their value-for-money proposition, providing quality products at an affordable price point, and has been a huge success.

You might not believe this if you look at Nitori’s stock price today but it was an unpopular company back then. According to Kiyohara-san, it was trading at 750 Yen per share at the time. One of the main reasons it seems, was that the furniture market was in decline, making it an unattractive industry to invest in. His thesis was that the market was extremely fragmented. The largest furniture retailer Ootsuka, only had a 5% market share. Nitori was the only vertically integrated manufacturer (others were distributors) and believed this could help them gain share as a cost-effective producer of home furnishings. Nitori was listed on the Sapporo Exchange so no institutional investor would touch it (since it would be impossible to sell). However, when he spoke to IR, he picked up on a key insight. While the Hokkaido economy, which was their main market, was not doing well and they saw a decline in same-store sales in the region, the 3 stores open in Kanto were doing very well. Providing a hint to Nitori's true competitiveness.

And it's funny because you can immediately tell he was built differently. After the research was done and when the fund launched he bought as much as he could from the failing bank and at launch it became 25% of his NAV. The stock tripled in a year and in 5 years the stock was a six-bagger. A year later it was a ten-bagger at which point he sold out. If he had held it till now stock would been a hundred bagger. But by 2003 Nitori was starting to get more institutional coverage and attention. He believed it was time to exit when. He says “When the party starts, that’s when we go home.”

So here was the first lesson, which is that investing in an unpopular, shrinking market can still make you a lot of money. In fact, during the time he owned Nitori the market size halved. He also understood the opportunity to buy shares from distressed sellers, especially for stocks that are listed on some regional exchange that no one looks at.

He offers a funny story about the Nitori Founder, Mr. Nitori. When he offered the founder to take him out for dinner, he refused on the ground that he doesn’t do that with brokers or investors. He couldn't care less about IR and believed that if the company delivers, the stock will follow. After asking many times, he finally agreed on the condition that the meal be under 1000 Yen. One thing Kiyohara-san remembers from this evening was when the founder said “if you find someone with talent, you chase them to the end of the world to get them to work for you, that is the job of the CEO”. The founder has been a maverick among listed Japanese companies. Even recently as Japan is going through its first bout of inflation in decades, he proclaimed publicly that he will not be raising the prices of his furniture. Man, what a character!

Now this was a home run but his other investments did well too. Small caps were in the dumps around the time he launched, but with some good fortune, it started gaining steam again shortly after. Moreover, he focused on investing in value stocks that were so cheap, without it being 'growthy' some of these did quite well.

Sept 1999- Feb 2000: getting burnt by the Tech Bubble

Kiyohara-san believes generally, top holdings in institutional large-cap funds were a good target for shorting. Most of these funds are typically just asset gatherers. These institutions use their marketing prowess to gather capital at quite a scale, which tends to drive the stocks up. Salespeople will then present clients with a slightly 'better' fund to move to. Why? because they charge another 3% commission! What that means is there will be redemptions in the initial fund en masse, this time driving the price of its top holdings down.

Thematic funds were the perfect target. Because there is always a new theme to get excited about and new themes will draw capital away flow from old themes (such is the average attention span of a human being, lol).

Though the issue is not unique to Japan the lack of financial literacy, the existence of only a handful of megabanks, stagnant stock market meant asset management was (and is) an industry with little in mind for the clients. To this day, most fund products in Japan do not have to report the name of the portfolio manager. Talk about accountability!

Anyhow, the flavor of the month in 1999 was the tech bubble and we all know how it goes. In Japan, Daiwa launched its Digital IT innovation fund which drew a lot of money and attention from retail investors. AUM continued to grow, grow, grow. "surely this is getting to silly levels" was his thought, and believed it couldn't be sustainable. That became his moment to short.

But nope, then came Nomura with an even bigger "Technology" fund with an AUM of 1 trillion Yen. By the time he realized, it was too late.

What's worse, Nikkei 225 index had its rebalance driving the already expensive stocks up even more. Some of the stocks he was short went up so quickly that he couldn't close his short position as he continued to get squeezed. It was a traumatic experience and his first real 'burn' on the short side. This was the first time when the K1 fund lost its popularity, labeled as a "failed fund of the IT bubble".

A month after Nomura's launch was the peak of the tech bubble, he managed to keep some of his short position and made some money back in the end.

Perhaps it was because of this small win that gets him into trouble down the road. The lesson he took out from this particular experience was "I messed up the timing, didn't think about Nomura participating".

Feb 2000- Oct 2005: Success in Real Estate Stocks

What helped post IT bubble was once again him focusing on an unpopular industry with a strong negative bias. This time it was real estate (and REITS). Real estate as an industry always had a bad rep because of multiple CEO arrests in the past, its cyclicality, and in the 80s it was notorious for Yakuza involvement (I still get asked about this sometimes).

During this period the market was concerned about the 2003 Problem in the corporate real estate market - a glut of office spaces causing a risk of declining rental yields. (I know ,it feels like we have a 20XX problem in Japan every year..)

The market cap of the stuff he invested in was so small that institutions avoided them.

This was when he started investing in REIT IPOs. Many had strong balance sheets and figured that some of them had high-quality assets that wouldn't be impacted much by such a temporary concern. Another reason he felt it was mispriced was that J-REITs as an asset class only started in 2000 - and many institutional managers weren't sure how to categorize this as an asset class. He believed that yield-hungry investors would eventually follow.

He also started buying up Real Estate Funds. The 2 main ones were Kenedix and DaVinci Advisors. Despite strong growth, these were only trading at 10 times P/E. He decided that growth could continue for at least another 3 years and proceeded to own 20-30% of shares outstanding at some point. These picks went up 3 to 4 times. The total sum he made was close to 20 billion Yen on these trades.

- And so it became a sort of factor bet, REITs became 70% of his portfolio at its peak. Come 2003 and the "2003 problem" was duly forgotten.

His exit strategy by the way, was apparently to sell these REITS when dividend yields fell below 4%.

Around this time, the fund starts to see strong interest from pension and other investors to board the K1J Fund train. ("He's Back!")

Oct 2005- Dec 2007: Small caps decline and shorts destroyed by foreign investors

Fun fact, the term in Japanese for when you get hurt both on your long and short book at the same time, is called a "matasaki" which literally means split at the crotch. This is what the fund experienced during this period. Around 2003 foreign investors started to get bullish about Japan. They believed that finally, the country was coming out of its lost decade.

Kiyohara-san didn't understand, he wasn't seeing much fundamental improvements in Japanese businesses. But foreign investors started flying into the country, and even as he spoke to some, he still didn't get it. As large caps gained steam, he initiated a short position against them. Inflow from foreign investors in the end continued til 2007! He took sizable short positions too early and as prices rose, so did his short exposure which reached 100% of NAV rapidly. This error in portfolio management meant he had no choice but to close his short positions no matter how convinced he was of the eventual declines.

This was an important lesson for me, you can be right about an idea but you need to be right about execution too (i.e. Portfolio management).

What made it worse for him was the "live door shock" of 2006. Which led to a violent sell-off in small/micro caps. His long exposure was 120%.

Context: The Livedoor shock happened in January 2006 when the Japan Securities and Exchange Surveillance Commission launched an investigation of Livedoor and listed affiliates for potentially violating securities exchange laws. This led to a selloff in Livedoor and affiliated stocks. Livedoor represented 10% of the TSE mothers index at the time so the impact was massive. This set off a chain of events in which investors started fearing that those purchasing on margin using Livedoor shares as collateral would start selling stocks to raise cash. Broker Monex then notified clients that they would assign a value of zero (from 70-80%) on Livedoor and affiliate's shares used as collateral. The fear spread to even those who were using other brokerages. Here's where things get crazier. Because so many individual investors tried to trade, the TSE could not handle the order volume and had to halt trading completely. This is the first instance in the world where a trading system was halted due to trade volume exceeding system capacity. The growth market never really recovered back to its high. (I'll save the details of why this occurred but might be fun for you to read about!)

Across his 3 funds, he lost a total of 60 billion yen on shorts between 2006-2008. Ouch.

2007 Dec - 2009 Feb: "A sick patient getting hit by a truck, 3 times"

Just as the fund narrowly escaped its "matasaki", it was followed by the 2008 crisis.

Whilst K1J Fund generated incredible returns from their bet in REITs and Real Estate and successfully exited from these. He still owned a lot of cheap real estate stocks in the fund. 3 holdings filed for bankruptcy and 1 went through an Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) The worse part? he owned 45%, 35%, 10% and 20% of the shares outstanding.

Needless to say, it was distressing and he lost weight.

The goal was no longer for him to generate returns in this period. It was simply to survive.

He never said this himself, but what follows is what you call an absolute shitshow. Or as he would put it, “like a sick patient getting hit by a truck 3 times”.

The fund's top priority was to reduce its leveraged long and short positions to avoid a margin call.

But to add insult to injury, their prime broker Goldman decided to change its margin policy to save themselves. (from 50% to 30%) Which could have been fatal for the fund. Fortunately, Goldman eventually agreed to only implement this in steps, which helped the fund bide some time.

The issue is that in a crisis like this it's not just one kind of risk that materializes, there are second-order and third-order effects which, in isolation might have a low probability. I believe, however, the odds of secondary and tertiary events no matter how unlikely will increase when the first 'highly improbable event' occurs. (You can also apply this to the Livedoor example).

Although not a surprise, the clients that entered in excitement when the fund was killing it in 2005 started redeeming (mainly pensions) and the fund lost half of its clients.

This created a new risk which forced him to reduce his longs which were mainly in small, illiquid companies. A forced selling driven by client redemptions would in effect make you dig your own grave.

So how does he try to solve this problem? He asks these companies to buy back their shares.

From its peak in October 2005 to its trough in February 2009 the fund’s NAV was -72% and its AUM -89%.

This is when you realize most people won't be able to replicate what he did. I wrote this in part 1. He decides to put almost all of his net worth in the fund to try and save it. He adds "Because that is the responsibility of the manager". Like a captain being the last to leave a sinking ship, an honorable and brave decision.

I want to reflect here because this is not something most of us could do. It's really easy to read this as a brave story and just say "wow, awesome", but never really understand the extent of how hard it was. (This is called the empathy gap in psychology where we underestimate our psychology to make decisions in a certain situation). If your fund is already down heavily, you have clients threatening to leave or have left, your prime broker changing the rules, and you're being forced to exit your positions at ridiculous valuations, are you ready to risk going broke to save it? Remember your morale at this point is probably at an all-time low. In a world where limited liability corporations are the norm (i.e. the damage to your personal wealth can be legally limited where, at the very worst moment most of us would use to escape) he decided to go all in.

Also don't forget, he's had to tell his wife he did just that! (which might've been the scariest part!). Apparently, her response to him telling her was "Didn't you also say that last week?" lol.

But the question begs, why did he do that? His confidence was far from crushed, and he was convinced if he closed his shorts and be as long as possible, that he would make alot of money. Why? because he knew a sudden decline will almost always result in a V-shape recovery. His game was to just survive until then. That is SOME confidence he had.

What’s amazing is that he went to clients telling them it would be foolish to leave now, "the fund can probably double from here".

In the end, from its trough through Feb 2018 his fund 12x ed.

As he reflects on this series of events, two points stood out to me.

80% of pension funds redeemed during this time, whilst attrition among individual private clients was very little. The fund had its own sales team to go around which I'm sure helped but still...

Many of their long positions were companies abundant with cash which enabled them to buy back shares from the fund when they needed to sell (Which IMO can only be done as a combination of its cash-rich balance sheet and the fund presumably being large shareholders).

Since this stressful event, he realizes that new clients will get in the way of performance. So he closed his fund to new customers (and you will see why this is important later).

2009 Feb - 2018 Feb: Revenge of the REITs, the dawn of Abenomics and BOJ ETF purchasing program.

The "sick patient who got run over by a truck 3 times" was now on the road to recovery. The fascinating part is he revisits the very industry that almost brought him to ruin, REITs.

This is where you see glimpses of him as an investor but with almost a political hat on.

REITs were sold off because the sponsors were going bankrupt during the Lehman crisis. However, the disconnect was that the REITs themselves should do fine as many had good balance sheets.

When the government set up a fund in 2009 to stabilize the real estate market, he made the call that the government would only save REITs which generally have solid equity ratios and not the sponsors or real estate companies themselves. When that happens, these sponsors will go bankrupt and the REITs get orphaned. In turn, these will need a new sponsor which, he bet that the government will make sure will not be taken over by another weak sponsor, which should then help these REITs be re-valued because of the 'upgrade' to a more stable sponsor.

He went aggressively after REITs whose sponsors had weak balance sheets and were on the verge of bankruptcy. When many of these REITs ended up getting sponsors with a much stronger balance sheet, the trade became a huge success.

Another point I want to highlight is how he did not bet on a single stock to make this work. Even as he focused on small stocks he managed to build a bucket of these stocks to express this opportunity. Whilst I don't know the exact numbers, the portfolio concentration on this "factor bet" was likely quite significant.

During the 10-year span post-Lehman, he's made a lot of interesting bets. Here are some selected notable longs during this period.

Pressance Corporation (Circa 2008?)

This company developed studio apartments in Osaka.

When he first came across it, it traded at a PE of 5 times.

This business didn't re-rate but the stock just ran because of its EPS growth. (was growing about 20% a year).

He likes this business because of its aggressive CEO and its strong balance sheet. As many players in the industry were defaulting left and right, the company used its cash to go after land being sold at a bargain.

This company also benefits from scale, as it got larger it could procure land for cheaper and negotiate better rates with contractors. Creating a positive feedback loop.

By the time he exited, there was still zero analyst coverage but in the end across his 3 funds, this was the most money he made on a single stock.

It wasn't just because he was right about the fundamentals, he was also right about the stock. He figured out the stock moves in a pattern. Every year, the guidance was ultra-conservative, which led to the stock declining heavily at which point he bought. By the second quarter, the company reaches its full-year target and the stock jumps, and he would just sell it. So he'd repeat this process in size 3 times. In the end, the stock dropped for the last time when the President was arrested (ultimately proven innocent) and was forced to sell his shares at which point Kiyohara bought again, but soon enough it got acquired at a premium by Open House. As a side note, you can see in his writing how much he respected the management of this company.

This was interesting to read because I often worry about the incremental buyer for these tiny companies, it’s good to see there is some hope that these overlooked stocks can perform (with some volatility) so long as earnings grow.

He also shares some of his large-cap investments, which in general were more short-term, event-driven bets.

2011: Olympus

The fascinating part for me was again, he was never just a pure equity investor. This was another instance where you see him seeing things through a political and macro lens.

Olympus came out with a huge accounting scandal. The TSE also puts them on ‘watch’ for potential delisting. Which drove the stock price down from 2700 to 400.

It wasn't a small bet, he bought 5% of the company. He can't remember why anymore but he sold it after it went up a little the same morning.

The same day a US News outlet reported one of the accused might have a connection with the Yakuza, which drove the stock down again (Lucky him!).

He thought the following: “Wow Yakuza huh, can’t get any worse than this” and proceeded to buy back the shares he sold the same morning.

Ultimately, he believed Olympus was worth much more than what it traded for, that even if it delisted this would be an attractive asset.

He arrived to this conclusion when he first looked at Olympus as a potential short! He felt that their endoscope business was just very good.

This part was the more fascinating point of this trade: As this was all going down he saw a news segment about Olympus in a positive light talking about their successful endoscope business. And he thought strange... How could that be? What’s the incentive to air such a positive segment when Olympus is going through an accounting scandal? With the scandal Japanese TV studios are likely to say NO to broadcasting such a program. Who could be pushing this? It led him to conclude that it must be government officials. As he continues watching the program he realizes Olympus is starting a new venture abroad in partnership with the Ministry of Economy. That’s when he realizes that the government has no interest in delisting this company. His other thesis was that he thought Canon would acquire Olympus for its life science business regardless of if it gets delisted or not..

In the end TSE decided not to de-list Olympus and the trade ended up close to being a 3x.

2012: JAL

It sounds like one Joel Greenblatt would relish in.

The flag bearer airline previously went into bankruptcy and was re-IPOing. Issue was that most investors had a strong negative bias of this business as a 'bankrupt' no-good business (many also got burnt before). Politicians and New outlets were all talking crap about JAL. The reality though was it was a reformed business with a pristine balance sheet.

So he bought as much as he could at the IPO and on the open market.

Feb 2018 - March 2020: Covid and cheap large caps

When the market fell through at the start of the Covid-era unlike the 2008 crisis the fund was in a much better shape to take advantage of this opportunity and there were nuggets that stood out. One of the thoughts I loved is if a meteor is about to hit Earth and the markets are down as a result, the only logical thing to do is go long. If you're short and you're right, well, the world is screwed anyways. On the other hand, if the world doesn't end, your long positions will do very well.

Another is around this time, he started buying REITs again. REITs were one of his main sources of success about a decade ago, but by this point, he wasn't following any at all. Despite that, he spent just an hour deciding what to buy after a chat with a sell-side analyst and his own team.

Sometime before Covid he was starting to feel that large caps were getting quite cheap so he’d been buying others like Sumitomo, Makino, Mitsui Chemical. When Covid happened he started buying the megabanks and his thesis was:

Management teams of these banks believe their own shares are too cheap. Kiyohara expected buybacks and increased dividend payouts.

That it was unlikely fintech would disrupt banking completely (which was the prevailing fear). Banking is ultimately about reliability and safety.

He believed that the incentive of the BOJ to increase the interest rate cap was to also to ensure regional banks (which were important entities in local areas) would survive since they were more likely to be hurt than the bigger players.

So directionally, he believed Interest rates were at the bottom would go up. Though not so much the short-term rates because most mortgages are on variable rates. So he figured the likely way the government will follow through is to get the long-term rates go up, which will be beneficial for banks.

Here was the other story that was funny and brutally honest. Normally he knows he should also research insurance companies as well to find the best opportunity possible - though he found it cumbersome so he had never studied the industry too seriously. So when the bank stocks came down during covid, he just went for it and bought the banks. He actively avoided talking to the IR of these Banks because this might put him off. (he felt they're often too serious and not too optimistic). Isn't it funny? I’ve never come across something so human and honest reading the biography of an investor.

When he went through covid, he wasn't really afraid of clients leaving this time and this comfort let him bet big on positions. One of the reasons was that his clients had gone through the worst of times in 2008 with him and stayed.

This reminded me of a Munger quote someone recently shared on X: "The best way to get a good spouse is to deserve one. The same thing is true about business partners. So I think that the relationships that are deep and enduring come from the hard times, and you frequently find that you get a lot more out of a good business relationship when things go wrong and you come through it with the person."

March 2020- June 2023: Post Covid, Return of Japan and curtain call

Even after the market recovered somewhat after the initial covid decline, he still felt large caps were cheap on a historical basis and remained bullish. He decided to buy more of his holdings, mainly the mega banks. This was around the time he started believing that covid was going to be bullish for the markets. He runs a thought experiment but the gist is that government handing money will lead to a huge increase in excess savings thus leading to some of that flowing into the stock market. And it did! Seems obvious today but not sure how many would've thought that a priori.

Fast forward to the summer of 2023 the moment came to close his fund. It was a 25-year run of a tumultuous journey but in the end, with a record that he can be proud of and puts him in the hall of fame. After recovery from his cancer treatments, there were moments in which he felt he was no longer willing to take big risks - his very strength, his level of intellectual honesty, led him to decide that it was time. (more on that later).

On Shorting:

This is a summary specifically discussing his shorts. If I'm being honest, I think I learnt more about investing through his discussions on shorts. Not that his longs were any less interesting, but the shorts helped me appreciate what makes stocks move and provided a stark reminder that fundamentals are a mere subset of what can make a stock move and understanding the deeper intricacies can make you money too. I think people who are good at shorting naturally have to worry about this more because it conversely poses a risk - where you can be fundamentally correct but still lose money on a host of other reasons that drive the stock up.

On brand with his usual unfiltered self, he starts his thoughts on shorts with a banger.

Hedge funds charge a 2/20 structure and to justify that you have to pitch your market-neutral, fund by saying that you can make money in down markets.

But that, this couldn't be further from the truth (he probably would've used the word Bulls***, but we don't have a word like that 😉 ), Admitting that he lost money frequently regardless of when markets were down or up!

He shares some of his general lessons on shorting, which has been the source of many pains for him though perhaps, also his greatest pleasures. As he wrote in the book when he was asked about what makes him happier? Being right on a long, or a short? He said shorting, it was possibly due to an ultra-competitive nature "Why wouldn't you be happy if you make money when everyone else is losing?".

Though he provides fair warning that he does not recommend shorting for individual investors in Japan, the information asymmetry is much too skewed. It's already a difficult game for professionals.

So what's the asymmetry? The securities borrowing/lending market for Japanese Equities is Huge outside of Japan. Professionals are privvy to more info via their prime brokers which can provide more information on the short interest for a stock abroad. Without this, it becomes very difficult to figure out whether you're sat on a landmine or not.

Having said that we already talked about how large caps held by institutions were a great place to find targets. This is where large Japanese asset managers can drive up prices of some stocks purely from inflows. This gets even more exaggerated with thematic funds which implies a certain excitement.

Shorts are the most dangerous in a bear market, in this scenario, his game was to maximize his long positions. Maintaining a short book means, your prime broker will usually give you a hard time in these moments and pssibly reduce your margin which also limits your long exposure. The other is that when the market turns and your shorts also move up, this might also force you to reduce your long position (to cover). Understanding this helped him avoid a forced error of omission. Imagine having no choice but to sell your longs which could have multiplied but you were forced to sell them after a little move up to cover your shorts.

After the painful mistakes over the years, the fund stopped maintaining a short book at the 10-year mark. His style evolution was that post-Lehman, he'd stop shorting baskets and take large short positions in max 3 positions, which worked out well. This he believed was the best way to short in Japan. He even goes on to say shorting baskets was a foolish idea. There is an inherent bias against diversifying. If you have an equal-weighted short book and one of the stocks halves, you’ll have to short more at a cheaper valuation to reach equilibrium. Another reason is unique to Japan, that Japan is an inherently cheap market, so to diversify is to increase your risk.

You think you're diversified enough? Think again. Things can correlate in the most unexpected ways. One that never occurred to me which I found valuable is that when he was shorting the 'expensive looking stuff' during the time there was strong interest from foreign investors, he was sufficiently diversified by industry yet, these were all held by the same foreign investors and thus he was insufficiently diversified at the shareholder level. So his 'diversified' shorts kept going up in tandem because foreign investors were all piling into the same stocks!

And he figures out the best shorting strategy that gets him to a win rate of 100%.

But before that, one last mistake...

This came when he shorted Fast Retailing which owns the brand many of you know, Uniqlo.

When the BOJ started buying ETFs in 2010, large weightings in the indices saw a disproportionate amount of inflows. One of which was Fast Retailing.

In addition to that he believed growth would slow as a maturing company. Basically he wrote off the growth outside of Japan. (I mean, I get it, I don't get too excited when Japanese companies naively expand abroad too).

In short, his mistake was to be too attached to the 'valuation' and missed the quality of the business and the caliber of the people running it.

So this became his single biggest loss on a short position by absolute value.

After this painful lesson, his winning strategy came down to a few points, it’s not only about the high valuation, you want a 'heated' stock with increased liquidity and identify when the stock has peaked. The peak he believes, is when the shorts start to cover their position. And the best is to initiate the short position when the short interest halved from its peak.

Some examples ideas:

Yaskawa (Circa 2017)

This was a textbook example of taking advantage of one his favourite hunting ground: thematic stocks

The main theme was robotics, and a series of automation fund launches drove the stock of this robot manufacturer up.

There’s not much more to this bet than this. They shorted at around 5500 yen and exited at 4000 yen.

Lasertec (Circa 2020)

This was not a fundamental idea, though it did fit the typical target for his shorts: expensive-looking large-cap.

He simply saw an opportunity through the lens of Japan's inherent tax rules.

The fourth largest shareholder was the widow of the founder who owned 4.24%

So he thought, what happens if she passes away too?

Japan's inheritance tax is the highest in the world, and her children will have to pay for it by selling shares.

In the end, this is really what happened.

This is an important theme for owner-operated businesses, in which inheritance can play an outsized impact on the stock price.

He provides an interesting 'insight' into how Japanese management may think in these situations. If for example, the business was small, cash rich and undervalued, the management might buy back the shares from the beneficiary. It's unlikely that the management will acquire or do a buyout if it trades below 1 times P/B to show respect to the founding family. Notice how in this case, the inheritance issue has the opposite effect and may be positive for the stock.

Aeon

Again for me, this was a lesson in understanding what makes a stock move.

The business itself looked fundamentally weak. Negative cashflows, barely profitable and with structural headwinds. Aeon was trying to build more shopping malls despite the shrinking population. It looked to be the perfect setup for a short but in the end, he didn't make much money.

the reason was that the shareholder base consisted of indifferent, passive investors. These weren't just index funds, but also retail investors going after Aeon’s shareholder gifts.

As a shareholder you receive an Aeon Owners card, which gives you cashback on purchases at their malls. More shares you own, the bigger the cashback AND if you've owned the shares for more than 3 years you also get gift cards worth up to 10,000 Yen...

Long Aiful / Short Acom pair trade (circa 1998)

Both were operating in the consumer loan industry.

When Aiful IPOd it was trading at 8 times P/E whilst Acom traded at 17 times even though it grew more slowly.

Aiful was listed OTC whereas Acom was on TSE1, which he believes caused the valuation disconnect.

Aiful continued to grow and they eventually gained recognition from investors.

What I appreciated most in this trade was his following thought: In hindsight you could argue that just an Aiful long would've sufficed, but the consumer loan industry had a lot of sketchy, regulatory uncertainty. So from a risk management standpoint, he believes it was a sensible decision to have made it a pair trade. (and in the end, the industry did go through tremendous turmoil)

Nihon M&A (late 2020)

It started trading at crazy valuations during covid. By the end of 2020 it was >100 times P/E and 75 times EBITDA!!

Fundamentally he didn't like it either given competition was increasing.

The problem was that employees could just walk out and start their own business.

SME succession is nothing new in Japan, growing at this crazy pace he felt, meant that the business was pulling forward (a finite) demand.

So he saw a risk of deceleration and eventual profit declines in the future - what’s the fair value of something like that?

Moreover, he believed when family members of the Chairman and CEO inherit the shares, there will be a massive inheritance tax (just like in the lasertec example) and they'll be forced to sell the shares in the open market.

In the end, he shorted 'some' - the stock declined after but because of an accounting scandal.

But this also became the turning point for him to realize that he was no longer capable of taking big risks on shorts and became a reason for him to close down the fund.

A graceful exit:

Perhaps most telling about his character was his decision to retire and wind down the fund not upon a failure but upon a success. When he shorted Nihon M&A and Lasertec, he made money on both trades – but not enough. His ‘failure’ in this was not sizing it as large as he should have and this was when he realized he didn’t have it in him to continue. To the very end, he let his intellectual honesty and self awareness dictate. It was a graceful exit to a hell of a ride.

By the end, he had an annual return of 20% over 25 years - a 93x! Mind you during this time the benchmark was almost completely flat. By this time a good chunk of the fund was his capital – the reward of a noble decision to risk his entire wealth during the Lehman crisis to increase his clients' chances of survival.

Some final thoughts on ESG that I found amusing

He has some pretty strong opinions here which boils down to the point that ESG investing is absolute nonsense. The G for governance makes sense but who are we as investors to decide what the E (environmental) and S (social) should be?

Especially for Environmental concerns the problems are complex and highly unlikely a portfolio manager can solve it. (truth)

From his standpoint – it seems like active managers are using ESG as a way to not get fired by their clients. No competent fund manager needs to have ESG, they just post good returns. period.

So those that do ESG investing are ‘everybody else’.

He drills into the ‘E’ to show what he means. The main one is CO2 emission reduction. This costs a ton of money to do. Individuals or groups (or investors) should not be the ones choosing who bears this burden, it should be done by the government and laws. I remember Buffett said the same thing. Letting certain groups and individuals decide which companies should do what creates unfairness and confusion.

A lot of topics people talk about are also questionable – the most recent example being microplastics. Remember the straw stuck in the turtle? This went viral but we don’t talk about it anymore. Turns out laundry is the top producer of microplastics.

The Japanese government is also confusing with their regulations around this topic, it is too complex and hard to follow – this also costs time and money for companies to report on.

On Governance he agrees: This is improving and seeing some progress in a good way. Believes this will improve shareholder returns going forward as well. Much of the credit goes to the activist investors.

The sectors where governance is not as relevant are in public infrastructure like railways and utilities -> these businesses are not trying to maximize profits and are there to serve the people. So he would generally avoid investing in them.

In Japan, you can make a shareholder proposal if you own 1% of the shares outstanding so the hurdle is low. This is great for governance. However, there are still some pitfalls. Cosmo Energy Company implemented a poison pill recently and did not acknowledge activist Murakami’s fund (a 20% holder’s) Voting rights.

This should not be permissible in court if a company chooses to exclude a Marjoity of Minority voting rights. This is not only for Cosmo Energy – this is a risk for any company listed on the Japanese Stock Market and should be dealt with seriously by both the government and the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Thanks for reading folks! If you enjoyed reading this I would be grateful if you could share and otherwise subscribe!

From here on are some bonus content from my paid supporters (whom again I wouldn't have been able to do this without, Thank you!)

Bonus Content

Here I'll be sharing things I dug up during my research and some other stuff from the book. I’m not going to lie, I spent way too much time on this part but I’m happy with what I found, and helped me understand his thinking further.

His past and current holdings (which he took over since winding down the fund) I could find. Close to 200 stocks.

His 8 predictions on Japan for the next 10 years

Mental Models - Biases and Probabilistic Thinking

His general framework on how he thinks about PE Ratio

How he reads annual reports and looks at the Japan Company Handbook