Book Summary: Our Investing Strategy, who does the market smile upon

Part 1: His investment philosophy

The Google translation of the title is “My Investing technique: who does the market smile on”. Neither is wrong, but I preferred to use the plural in the spirit of his appreciation for his partners. Book Summaries I realized through this, are not easy. Taking notes for yourself and summarizing for someone else is an entirely different exercise. I have no regrets though, as I felt it was almost an obligation to leave the insights from one of most successful Hedge Fund Managers in Japan, a true Made in Japan Investor of which there are so few that get talked about outside the country. This took a bit of time since I ended up doing some fact checks and full-on research.

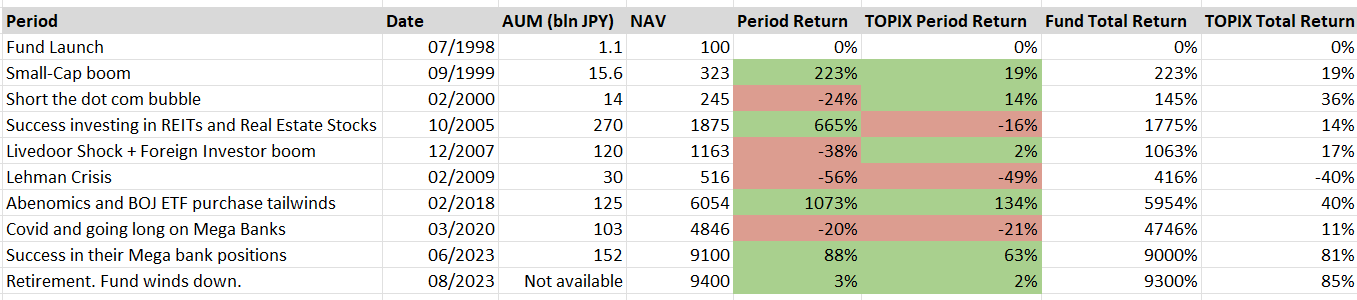

He goes by the name of Tatsuro Kiyohara, who was the CIO of Tower Investment Management, which ran the flagship K-1 fund that compounded 20% annually during his 25-year run (that’s 9300%). Compare this to the TOPIX which did an annualized return of roughly 3%.

But its not just the numbers that he posted that were inspiring, the journey to get there was a tumultuous one that would be almost impossible for us to replicate. He is built differently. Who else is willing to pour in almost their entire net worth when the fund is down -72% in an attempt to save his fund not just for his sake, but for the clients that decided to stick with him amid all the redemptions? Action speaks louder than words, this wasn’t quite the man of simply money, but of honor who was ready to sink with the fund. Many funds were down that year, but it’s about how that wasn’t pretty for him which he describes as “A sick patient getting hit by a car three times”. This is a story of persistence. He is no stranger to life’s challenges either, In the final years of the fund he ran it as a survivor of throat cancer and having lost his voice. He was rewarded with this fund-saving bet. Today he is left with an estimated net worth of 80 billion yen.

Based on what I found during my research, he is described as a humble, soft-spoken man who was a good listener. He didn’t seem to have an obsession over the money itself, but rather an obsession with being right on his investment decisions. His fixation to get as close as possible to the truth wasn’t just in finance, growing up he seldom understood people who admire historical figures (Sakamoto Ryoma, in this example) how do you know what kind of man he really was? He was unique and uncharacteristically bold in a country that favors stability over risk, especially so in the world of Japanese Finance. At the launch of his first fund, 25% of his assets were in one single position.

His flagship K1J Fund (he had 3 funds) was a Long/Short Fund but doesn’t quite do justice in describing his style which went through an evolution. On the long side, he was a true bottom-up value investor in some sense but also not in another – on the short side, his strategy was ever-evolving making it hard to define but that is why I learned so much. In many ways he was a rulebreaker, as a sizable Hedge Fund, he would take concentrated positions in illiquid small & micro-caps and at times, go against the traditional wisdom of intelligent investing, like taking bigger positions in a stock before the research is complete.

What I enjoyed so much is that he walks you through his thought process on investing and even certain trades he made, it’s as raw as it can get from any investor biography. There are some unique and insightful sections discussing the importance of Bayesian inference and cognitive biases in decision-making – and you can see his delight for the counterintuitive- A word he repeats in English throughout the book (for lack of a better translation). As a retired professional today, he has little incentive to sound professional or market his fund and he’s willing to share some truths that most managers aren’t willing to admit. He wrote this in this authentic way which also made this book that much more enjoyable – he would tell his stories like one of your fun uncles at family gatherings. In later parts of this summary, I’ll try to share some of these.

Usually, if it’s such a great book, I’ll just tell you to go buy it. But because the book is in Japanese and I’m unsure if or when exactly the English print will come I’ve decided to write a summary. I don’t want him to just be a book that sits on the bookshelf of Japanese bookstores. There will be nuances that will be lost unfortunately, but to share as much as possible I’ll be splitting this into (probably) 2 parts.

Before I start, a couple of things:

None of these points are in order, and likely will not convey the full message that Mr. Kiyohara intended.

The notes I highlight are based on what resonated with me so there’s a natural bias (as he would say) on the information here in addition to the bias that he has. There is an overlay of how I interpret his wisdom.

Italics = my thoughts and reflections

Who was Tatsuro Kiyohara?

Born in 1959, he spent most of his youth in the coastal Shimane Prefecture of western Japan. At age 18, he moves to Tokyo to study at the most prestigious university in the country, Tokyo University. Being surrounded by people that he felt were much smarter than him, he resolves to remove himself from this competition and to achieve success by saving money and making it big in the stock market. In some ways, he expresses this attitude of ‘dumb competition’ investing by focusing on micro & small-caps too. Soon after graduating, he joined Nomura as an analyst – which back then had a reputation for pushing bad products to clients like hot potatoes where only the broker wins from all the commissions. This became a conflicting period where he started reflecting if there was a better way to create a win-win situation for clients. During his time there, he was sent abroad, studying for an MBA at Stanford followed by his placement in the New York branch in Sales. New York seems to be the turning point, he came across the concept of Hedge Funds, a still obscure concept back in Japan, but resonated with his solution for a true win-win. By then he was already widely recognized for his abilities in the organization.

During his stint in New York, his clients included the familiar hedge funds we’d all heard of. One of which was Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management. Meeting Tiger was perhaps the first instance he decided that he wanted to do something with hedge funds, he would spend his days talking stock at their office. Tiger appreciated him too – one time he realized that Tiger was short a stock, Kawasaki Steel, and also realized Nomura was attempting to ‘promote’ the stock (what you call ‘pump’ these days), he almost had to fight with Tiger to convince exiting and that the stock was going up regardless of fundamentals which they finally obliged. This stock 3xed not long after. Not a surprise that he was invited to Tiger’s annual party to be awarded best salesman of the year. This experience on the sell side should’ve been a reminder that stocks don’t just move on fundamentals and assuming so can be a brutal mistake. (Spoiler alert: he makes this nearly fatal mistake) This wasn’t the only famed fund he crossed paths with – one of his largest clients for Japanese Convertibles and Warrants was Ed Thorpe’s Princeton Newport Partners which was soon engulfed in its RICO debacle.

His boss at Nomura was the famed Yoshitaka Kitao, now the CEO of SBI and before that the CFO of Softbank. It was clear there was a deep love and respect for him whom he calls his ‘forever boss’, when Kitao-san left for SoftBank, it wasn’t long until he decided to leave as well.

He then joins Goldman Sachs Japan covering convertibles and is shocked by the cultural difference working at a Gaishikei (Foreign firm). In my experience, this kind of shock still happens today. This was also around the time he actively started researching small-cap stocks to invest for himself. He held on to some of them for 30 years which went one to become multi-baggers. But this wasn’t quite yet the Genesis of “Kiyohara the Hedge fund manager”, he would take other jobs which expose him to M&A, Private market, and other things in the interim. It wasn’t until he turned 39 that he launched his own Hedge Fund by joining Tower Investment Management, a Japan-based organization, as its CIO.

K1J Fund returns:

The performance of his fund was volatile, and the fund had a near-death experience. Yet he somehow manages to return from the dead and handily beats the market. It is easy for me to pull up these numbers but take a moment to feel what an agony it must’ve been for a few years. Most people would’ve folded then and even after surviving, most wouldn’t be the same after. He does confess there were moments where he lost his confidence.

The performance isn’t yearly but by periods that he reckons were pivotal. I couldn’t find his yearly returns so based this on whats mentioned in the book. I’m just using the last day of the month for each data point so some inaccuracies.

I couldn’t find exactly when his fund closed, which only mentions Summer 2023 so I guessed the end of August.

Topix returns are based on a simple price return.

Tips on investing for individuals

He shares some wisdom and practical tips for individual investors.

The first of which is that there is no need to spend so much money on research. (especially for individuals). In the last years of his fund, he stopped using Bloomberg and Nikkei’s QUICK altogether. Doesn’t think there was much impact on his performance. As an individual investor, the better use of that money is to simply invest in stocks. If there is one thing worth spending, he recommends: The Shikiho-online basic plan. (which is the online version of the company handbook, and the subscription is 1100 Yen/Month which you can find here) For the most part, you don’t need any other subscriptions.

He does admit as a professional he was subscribed to business publications like Nikkei, Nikkei Business, Diamond Weekly, and FACTA. He’ll probably keep his subscriptions to Shikiho-online and FACTA forever. For the individual investor, however, these mass media-type outlets are almost unnecessary.

The definition of finding an investment idea is to find what is not reflected in the stock price. This is the so-called variant perception. The game is to figure out when you’re in the minority. This doesn’t always mean that because everyone is bullish, that you being bullish isn’t a variant perception. If for example the market expects a company to grow by 10% a year for the next 5 years, and you believe it will be more like 30%, you are still in the minority.

It is more difficult to thus have a good investment idea in large caps because its harder to figure out what’s priced in.

From an opportunity cost standpoint for an individual investor, the return on time is so much better researching cheap micro & small-caps with the potential to grow. If you had an hour with the CEO of a large company or a small one the likelihood you will get more valuable insights (your alpha) is much higher in the latter. In general, you also won’t lose much if you’re wrong here, these companies aren’t priced for growth anyway. For him personally, he tries to avoid investing in stocks that have already gone up as much as possible.

So in many ways for the individual investor, there is no better place to invest than in small and micro-cap stocks. Especially if you’re Japanese, spend some time looking for exceptionally cheap companies and investing in them.

The goal is to find businesses that you can own for 3 to 5 years - and you’re looking for stocks that at least double.

To him, the most important trait as an investor is how willing and able you are to learn from your mistakes. i.e. having good feedback loops.

You don’t need complicated probability theory but thinking in probability helps – it takes you away from living in a world of 0 or 100%. Even if you ascribe an unlikely event say 5%, this opens you to to recognize it is still possible. There are no 100% truths, at best they are 99% truths. This is true in general, but the realization is all the more important when it comes to investing. He highlights the importance of bayesian inference, and how such probabilistic thinking applies to investing.

For the individual investor, he also does not recommend shorting - there is too much information symmetry and risk that is not worth your time. Professionals are privy to expensive data to manage this risk so there is too much of an unfair advantage.

For aspiring fund managers, the larger you get the more disadvantageous it is to invest in small stocks – so the best way to have a great track record is to invest in them when your fund is still small. Which will help in marketing the fund.

And a warning: he urges however not to convert to a full-time private investor so easily. The psychology required as a full-time investor is different from a ‘part-time’ investor with a salaried income. Investing whilst having a stable salary is very different from putting all your wealth on the line. This becomes very clear in a market downturn. The fear you feel will be different.

And on hedge funds: you absolutely need PMs with skin in the game, any fund with the PMs only investing 10% of his net worth is not a real hedge fund and recommended not to invest in such funds.

On the flip side, too many allocators are concerned about short-term returns and risk-adjusted returns. The job of a hedge fund is to take on risks not to reduce them.

On his Long Strategy

Though it is hard to verify, the book seems to suggest more of his success came from his longs. The insight here does not veer off too far from Buffett’s principles of value investing. He had a bottom-up approach looking for undervalued companies that can grow. The logic of investing in very small companies is clear and he would continue to do this even as his fund grows. To the extent he could, he did so without increasing the number of positions but investing more in his existing positions. Naturally, he would own a large stake in each company and held a concentrated portfolio. It was pretty typical for his fund to own more than 5% of the firm at times even up to 30%.

This had its risks but one way he saw it was that because the float at that point was so low, no other fund could buy it, which meant that he ended up with a highly differentiated portfolio that other funds couldn’t replicate.

At least in the early days, he decided it wasn’t worth doing large caps – it’s a more complex game to gain an edge so he focused on simpler games.

Investing in micro-caps (and small-caps)

The difficulty of figuring out what is priced in becomes increasingly harder as you target larger companies.

In general investing in large caps is a far more complex endeavor: it’s difficult to figure out what is implied in consensus – following the news and speaking to analysts won’t be enough. The more people following it the less likely you’ll be able to find an edge.

On the other hand, with Small & micro-caps, no one cares about them, which means it’s a simpler situation and less effort to figure out what consensus is pricing in.

In small caps where he defines this as a market capitalization of below 50 billion Yen (300 million USD today) there is a surprising amount that the market misses and most businesses are cheap and priced as though earnings aren’t going to grow. But if you can find companies that can grow among them the returns will be explosive – this was the key insight into his fund’s success. He felt that the downside to this strategy was capped, If you decide this cheap growth stock was indeed a non-grower you’re not going to lose much because it’s already priced that way.

To summarise the strategy: find stocks priced as if they won’t grow, and among them figure out which one will.

And the non-efficient market hypothesis: In his experience, most small cheap companies are overlooked. So even when there’s information readily available on the company website, the implication is that no one is looking at those anyway, that’s why it’s cheap (and illiquid).

He almost entirely ignored the TSE Growth Market (previously mothers), too many small, expensive, unprofitable companies and the hit rate was too low. He seems to agree with the notion that IPOs were biased towards overvaluation because VCs are trying to exit at the maximum value possible.

A great hunting ground was looking at unloved industries: which is a lesson we’re often told but the stories were just hilarious.

One of his favorites was the real estate industry which had a bad reputation. This is true, among some there was a level of corruption and involvement with the Yakuza.

Some things he saw:

One of the CEOs of a company he owned got arrested for unclear reasons – eventually proven innocent, the company got acquired.

Another company had a CEO who got arrested while taking drugs at his mistress’ residence – this one went to Jail.

Another company Pressance was one they owned, and the president got arrested but was eventually proven innocent.

But this provided him with fertile ground to hunt for stocks. In fact this was how he found Pressance Corporation which became one of his biggest winners.

One of his first investments with the fund that falls into this archetype was Nitori, which is a household name today but when he first invested nobody touched it. It was a Hokkaido-based company, and the furniture market in Japan was shrinking. What he realized though was that the market was very fragmented, and he saw Nitori as the one to take market share over time with an exceptional founder. Which proved to be correct. His investment in NItori 10xed all the while the market halved. The lesson here was that even with a shrinking market if you find the right company, you can generate strong returns. No doubt there are some diamonds in the rough.

If he had held this business until now, the stock would’ve been 100x. He explains that his work is to find cheap stocks, which he felt was no longer at some point.

In the end, 90% of investing in Small/Micro-caps is about Management

Heres what he looks for

Operators with a growth mindset

Talented employees that are aligned with the CEO’s Vision and Mission

Doesn’t get crushed by competitors

A widening core competence (read = Moat) as it grows

Not in an industry where you’re pulling forward demand (There is a finite pile of demand that once absorbed will be gone, he points out the Japanese M&A industry as one)

The management is impeccable with their word that is, they do what they say

Companies that have positive feedback loops (I added this one from another section)

And to him the most important by far is the first point, assess if this is the type of leader that has strong ambitions to grow the business.

He shares some funny stories about management teams he met:

With one company, every time he requested a meeting with Investor Relations, the CEO showed up every time without fail which he found strange. Eventually, though this business got caught in an accounting scandal and went under. Maybe if the CEO shows up too readily you need to be careful. Another business had zero interest in doing IR, showing up in their factory uniform, and wasn’t too friendly. One day however they show up in suits! This business also didn’t too well.

He met another CEO didn’t even talk about his business and the conversation ended after 20 minutes. Remarkably he invested anyway because it was so cheap. After investing though he went to dinner with him and all he talked about was how eating fish makes you smarter and that’s why Japanese people are so smart. This one didn’t work out either.

You want unique/outlier CEOs but not too strange either.

There are mavericks among them. Founder of Zensho Holdings (the operator of Beef bowl chain Sukiya). This was an unpopular stock that IPOd. The first thing he saw when visiting the founder’s office was a bench press. He was ‘ripped like Popeye’. At the meeting, all he talked about was how superior a food a ‘beef bowl’ (Gyuudon) was. If Japanese people had eaten enough beef bowls and benchpressed enough Japan wouldn’t have lost the war (LOL).

One time one of Kiyohara-sans employees told this founder he’s also been going to the gym, he immediately challenged said employee and tested him with a ‘lariat’ a type of wrestling tackle. The key is to find a CEO who knows his wrestling moves.

The IR was also interesting. In its mid-term plan, they even included the P/E multiple the company should be trading at in 5 years.

So what do you think happened to this company? I’ll let you look it up yourself. The ticker is 7550.

As he once reflected on his portfolio, he realized that the business and its management was like looking at himself in the mirror. If assessing management correctly is the key to investing, also understand that there is a self-selection bias. If the Founder and CEO is that much more brilliant than you – you won’t even realize how brilliant he is. That said you’d never invest in a ‘dumb’ CEO, so ultimately you end up selecting people ‘on your level’. This it appears, to be the reality for investing in microcaps.

This is one of the more profound and humbling insights from this memoir. The ability to find the right company is more tied to you and your development than you might think. Given the size of these businesses, the rear-view mirror is even more useless to finding the right business. In this respect, this insight is akin to the way VCs invest.

On Valuation and the definition of cheap

He was adamant about that whether large or small – he had no interest in buying an expensive business. If the P/E was too high, that was a pass.

Over the years he tried building various growth models and realized this had almost no benefit to making money so just stopped. Was a waste of time.

He screens for such companies by finding a high net cash ratio which was just net cash over market cap. (So basically net-nets).

He also liked to invert the problem, by looking at the current P/E of the stock you can figure out the kind of earnings growth it implied. No rocket science here – he tries to figure out the Terminal Multiple with a Perpetual Growth model. For example, if the risk-free rate is 2% and the P/E is 10x that implies a terminal growth of -8.2% all else equal if earnings growth was -3.1% instead then the P/E should be 20x. (Yes this is all negative growth)

The 40-year average of the risk-free rate is about 1.7% in Japan so that sounds fair to him. Also, he says, forget about the concept of equity risk premium - this is just a banker’s term to underwrite uncertainty. If you’re uncertain just model that into your earnings projections.

There are high-growth businesses where you’ll need a multi-stage growth model but it takes more work to project so far ahead, it’s easier and more efficient to research low P/E companies.

So in general he ultimately believes anything with a P/E under 10x is too cheap given the current interest rate – even if this expands to 3%.

He doesn’t look at P/B where Investors may be calculating the liquidation price which can be inaccurate.

The point he thinks many miss - if a company is loss-making would the hypothetical buyer buy the assets at face value? And say that the business is a decent profitable business – no one’s going to be looking at the P/B they’ll be fixated on the P/E.

So his conclusion: Loss-making or Profitable, P/B ratio isn’t very useful.

In fact, his experience is that most value traps come from those with low P/B companies.

One of the main metrics he focused on was what he called cash-neutral P/E multiple

His definition of net cash: Current Assets + Marketable Securities x 70% - Liabilities

Note that he remarks this is not one size fits all – there are sensible adjustments depending on the business. For example, you probably won’t be able to sell inventory at face value.

He discounts 30% of marketable securities, which he assumes as the tax upon sale.

He uses this to reach a cash-adjusted P/E (“cash neutral” P/E Ratio) a more comparable metric across companies with differing balance sheets.

There are some caveats:

One is that this disregards any value of Non-Current Assets.

Another is capex cycles – if a business needs a large investment for a new facility that cash won’t be returned. Some firms these days have old facilities. So it’s worth checking if the company’s facilities aren’t too old that it needs updating.

Same with REITs, if underlying assets are old, ‘cheap’ might not be really ‘cheap’.

Climbing the valuation ladder: Where the explosive returns come from

Essentially he highlights the archetypical journey of a multibagger, a combination of a low starting valuation, growth and goes up the valuation ladder.

This was his trick. The crux of it was to find companies with a low starting valuation that can grow and re-rate as the business gains more attention from funds and analyst coverage.

He then brings up an interesting point he was very open about and almost no manager with institutional mandates is willing to admit:

In the early days, he did a lot of research before pulling the trigger, as the fund scaled however the focus became to buy most of the float of these tiny companies early.

If it’s cheap, if you buy it early the losses will be minimal anyway so invest sooner rather than later. In some cases, spending too much time figuring out the odds first could reduce your returns from 16x to 5x for instance. This is a failure. The opportunity cost of missing this is far larger than the absolute losses of being wrong. In fact, many companies that didn’t grow (i.e. a mistake) still eked out returns because it was so cheap in the first place.

In the end, even as a professional, you will never have ‘enough’ research.

Some were so illiquid it can often take an entire year to take a full position to minimize market impact.

Here’s an interesting perspective about illiquidity: he adds when he buys most of the float – shares become so scarce that when other investors are suddenly interested they would pay a higher premium. In essence for the right companies, illiquidity = scarcity value.

And obviously, there’s a big risk to this and most risk departments won’t even let you do this. So he had to get creative with his exits which at times were a little questionable depending on who you asked. There were many occasions he would ask the businesses to buy back his portion of shares which also turns out to be more tax efficient than a sale on the market I learned. The book doesn’t mention this and something I was taught from someone I know, is that when one of his stocks hits a limit up, he’d use that opportunity to get rid of a big stake but only does it a couple minutes before market close. Which gave him some notoriety among investors.

Risks of small/micro caps:

Buyer beware, it is also important to be cognizant of why these things can be so cheap, he discusses a few potential reasons. Some of these never occurred to me, like their incentive to keep the valuation low because the inheritance tax is so high in Japan. You can get taxed up to 55% which is the highest in the world. As you will read in a later section succession and inheritance can play a big role in the markets.

Illiquidity discount

Many businesses are small suppliers to a much larger company

It operates in an industry with low entry barriers

Limited talent within the organization

Succession issues and nepotism – the son of the owner can be a dumb ass

Because no one notices them – the likelihood of a fraud/scandal is higher

When the owner retires, this person may pay out a massive retirement bonus

Because it’s an owner-operator and harder to take over, no one keeps them in check and may screw up

When there is an accounting fraud, the damage will be large

They don’t have the resources to expand overseas

They have an incentive to keep their valuation low to minimize the inheritance tax.

Investing in Large Caps:

Kiyohara-san talks largely about small-caps but it isn’t true that he completely disregarded large-caps either. One of his bigger investments during the covid-era was in the mega-banks. There were some others which I will share with you later on. Despite the difficulty of figuring out what consensus was, my impression was that he zero’d in on finding a singular insight to trade on event-driven opportunities. He says himself, that to win in large-caps you mustn’t miss the short window of opportunity that the market presents. Otherwise, large-caps were main targets for his short positions.

All It took was one hour of research

In 2017 the news about Kobe Steel came out about its data fraud.

The total research dedicated to this trade was only 1 hour before the market opened. But in that one hour – him and his 2 colleagues dedicated every second to this stock to gain one single insight and went long.

In Large caps, there will be moments where the market gets the probability of outcomes wrong – it’s a narrow window but this is the opportunity.

Now this example was something I found extremely fascinating. On the long side, he was a “long-term” value investor most of the time. There were instances though where he would make these profitable trades. He even bought Olympus, sold it, and bought it all back in the same day. (He does this for other stocks too) For any long-term’ investor investing in a company after an hour’s worth of work may be considered heretical. Should everyone start doing this because he can? No. Note that these trades also came at later stages of his fund and experience matters.

On meeting George Soros:

This was short and I wish there was more context to this but 2 comments he remembers:

Soros tells him:

“The Hedge fund world is too institutionalized, Whenever a PM wants to take a risk the risk manager jumps out immediately to ‘manage your risk’. Remember Kiyohara, if you have a lot of confidence in your idea the whole point is to take that risk bet big, do you understand that?”

“Do you want to make money? Or do you want to leave a good track record? Which do you choose? The two aren’t the same”

Shortly after this conversation, one of Soros’ team calls him to invest in his fund. The amount was too large and he didn’t want that risk so he turned him away.

Soon after they came back with a smaller ticket size, with an option to invest more at a later date. He felt this was too cumbersome so he turned him away a second time.

Its getting looong so I’ll end it here for now, hope you enjoyed the read! I wanted to first go over his investing philosophy but theres so much more to share so in an eventual Part 2 I’ll get into discussing some of his trades, and shorts which dare I say was even more interesting.

" If there is one thing worth spending, he recommends: The Shikiho-online basic plan. (which is the online version of the company handbook, and the subscription is 1100 Yen/Month which you can find here) For the most part, you don’t need any other subscriptions"

Is The Shikiho-online basic plan available in English as well?

Great read! Thanks a lot :)