Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only. Nothing should be considered as investment advice or as a guarantee of profit. It may include some errors, please make sure to do your due diligence. The opinions expressed are those of the author and are subject to change without notice.

Disclosure: The author currently owns shares in the company as of 15 September 2024. The security could be sold at any point in time without prior notice.

Japan seems to have some kind of ‘problem’ every year. As in, we have a ‘2024 problem’, the 2025 digital cliff, the ‘2027 problem’. I know what you’re thinking, we are severely lacking creative names…

We’re 8+ full months into the year, but I’ll take a jab at an important deadline that we passed in Japan. The so-called “2024 Problem”. This I guess, will be my first ‘thematic’ post. Today I’ll be discussing:

The background of the issue, what this means, and why it happens

the potential opportunities that arise from this

It’s worth discussing as I think it gives those new to Japan a better understanding of the unique market structure that pervades the nation today thus leading to different industry dynamics one might not find elsewhere.

I was originally going to be brief on the industry issue itself and discuss a specific idea but I’ll leave that for Part 2 since it got quite long. I liked the idea bc it trades at a single-digit cash-adjusted P/E and 40%+ of market cap in cash.

The 2024 Problem

This issue relates among others, to the logistics industry where the government capped overtime work to 960 hours a year (or 80 hours a month) for truck drivers across the nation. This came into effect in April of this year.

There seems to be a misconception that this was only related to logistics. The origin of this was the ‘work style reform’ policies by the government which were initially applied to all industry categories back in 2019/2020. This in effect encouraged a ‘healthier’ way of working in Japan. However given the lack of feasibility in some industries, certain professions were given a 5-year window to adapt. These were professions like construction, medical, and truck driving/logistics. To be clear 960 hours is still insane and unfortunate to see we’ve even had to come to this.

Truck drivers historically have been stretched, though not dissimilar to other countries, they are heavily underpaid, work long hours in bad conditions. METI reported that the average hours worked by truck drivers are in the range of 2500-2600 hours a year as of 2019 compared to an average of 2076 hours across all industries. This despite the average annual income at that point was lower for drivers at between 4.2 to 4.6m Yen versus 5m yen across all industries. Mind you these are the ‘official’ statistics and in reality the amount of overtime could be higher.

As a result of the capped hours though, the logistics capacity of trucks is predicted to be reduced by -14.2% in 2024 and projected for -34.1% by 2030.

Naturally, with this comes the potential risk of disruption, in a time where e-commerce in Japan still has room to grow. (E-commerce was still 9.13% of retail as of 2022) and businesses are increasingly creating an omnichannel customer journey making logistical needs more complex. Logistics touches almost every kind of service, and an increase in rates for logistics will likely result in an inflationary problem at the macro level, and a cost pressure for businesses at the micro level.

This industry is structurally different to that of other countries and has shown to be less efficient than other developed countries (Ugh, surprise!). Loading efficiency was estimated to be 39% in Japan compared to 57% in the EU. I’ll highlight a few of these fundamental differences based on what METI found because I believe (therefore not necessarily fact!) it’s plausible this caused some of the problems we have today.

Fragmented industry

This is the case for many countries. The trucking industry is fragmented as hell with low barriers to entry. The trucking association reported in 2018 out of 57,054 trucking companies 52% of them owned less than 10 trucks. Just 7% had a fleet of 50 or more. This can make it difficult for companies to benefit from scale and is likely leading to intense competition. Truck drivers are willing to take on additional work that are not originally agreed upon and may sometimes do it for free. The customer has significantly more negotiating power and may threaten the drivers to switch to another provider - and this creates a huge imbalance as you’ll see below. Could this be because of the dominance of the Shoshas as Japan was rising? Maybe. But it’s clear this is a real issue.

2. Skewed delivery times and strict schedules.

As a result of the above, delivery times are heavily skewed towards the early hours of the day to avoid traffic on the main highways to meet the strict operational plans of such large customers. With the negotiating power they have, corporate customers are demanding on-time delivery usually by the hour or even in 10 minute increments! This kinda makes sense because of the ‘just-in-time’ philosophy that became a backbone of industrial Japan. For that to work, every part of the supply chain has to work in concert, including the driver.

3. Complicated distribution networks

To make it worse, for many industries in Japan, be it food, industrial, medical or anything else, the supply chain is insanely complex. It can have layers of wholesalers. It is common practice to have secondary and sometimes even tertiary wholesalers in the value chain which makes it often confusing and opaque in terms of communication between the parties, including drivers as well. Whilst most countries have SMEs as the backbone of their economy, what stands out for Japan is that their ecosystem of very small business owners is extremely high as a proportion. Secondary wholesalers are usually needed to reach these extremely small businesses who also often only order in much smaller quantities than what a primary wholesaler might be used to. This level of fragmentation also makes it virtually impossible for primary wholesalers to cover ground efficiently, which is why the secondary (often regional) distributors justify their existence. People have argued that the internet would ‘fix’ this, but the reality is the market structure is such that these secondary/tertiary wholesalers are still relevant today for small businesses and change is slow. These small bizes need to procure a wide range of needs to keep competing, but they don’t have the means to source all that themselves. Secondary wholesalers take a crucial role in simplifying that process including some back-office functions.

I do apologise since this is Japanese but take a look at this market share chart of the food retailing industry just to get an idea. The top 3 are Aeon Group, Seven & i holdings and Family Mart with an estimated 10.4%, 9.9%, and 3.5% respectively. But this is somewhat misleading since within these groups are multiple subsidiaries that likely have different suppliers. Retailers below the top 5 effectively have a share of 1.5% or less. This type of market structure isn’t just for food retail - it happens across a variety of industries.

4. Companies don’t like to use Third Party Logistics (3PL) here

The first point is that multi-modal transportation is not really a thing here. I was surprised too. Freight via rail is less than 10% of the volume transported on-land. Compare this to the US or Europe where this figure is 50% and 20%. Economically there was little incremental benefit to using rails over truck as a mode of transport. Especially because with trucks you can pinpoint a more specific time for delivery. So with a more ‘straightforward’ supply chain, this also means the need for a 3PL service wasn’t there.

In reality, 3PLs are just not popular in Japan. We have a high portion of 3PLs that are spun out of keiretsu’s (conglomerates) - they have an estimated 32% market share within 3PLs given their historic dominance in Japanese businesses. This is a unique industry structure compared to the RoW. The issue is that many of these are not incentivized to be run well as they’re effectively a glorified in-house logistics company. Customers have low trust in these services. Because there’s been so little interest in this service for so long, they’re also finding it difficult to find the right talent and skill set that can improve this. They remain dominant seemingly only because of their long-standing business relationships with customers and ‘shigarami’ (しがらみ)i.e. the friction caused by personal relationship, management ethos etc among them.

This is a real problem as 3PLs run well, can function as a demand + resource aggregator and at scale can enable a more efficient logistics process. In turn, these would be the ones who could afford to invest in automation + digital to pursue and encourage further efficiency in the industry…

5. Lack of DX

Look I’ll keep this short because otherwise, I’ll have to complain about this for every industry I write about. A lot of the orders for logistics services are made through e-mail, phone and fax. (😭). The use of such digital systems is more advanced in other countries. Japan is behind at all levels here, whether order management, route planning, or warehouse management. The stock idea i’ll discuss in part 2 relates to this.

6. Ineffective loading/transporting principles accepted as standard practice

This one was interesting since it never even occurred to me as an outsider, this topic itself could open a can of worms but I’ll focus on one that caught my attention and what ‘seems’ like a low-hanging fruit to make things more efficient.

Did you know only 12% of loading involves standardized pallets in Japan? Compare this to the US where that figure is 32% and in the EU where it’s 54%. The use of standardised pallets can reduce the loading times significantly compared to using manual loading which is basically tetris but trying to fit as many boxes in a cargo. (METI estimates a 75% reduction) The issue seems to be that the market discourages both the use of pallets in Japan and the use of standardized pallets, unlike other countries.

This is suspected to happen due to logistics companies being resistant to using such things and the lack of multi-modal transport (i.e. no rail) also means there is less incentive for it to be packed into pallets. Unlike in the EU where there are many rental pallet companies, the norm here is for the shippers to have their own pallets so it’s cumbersome. This BYOP (Bring your own pallet, yes I made this up) means that most use pallets in different sizes - which makes it difficult to load items neatly unlike when everyone uses a standard pallet size.

7. Warehouses are also struggling

Not just the drivers but the warehousing industry is also having similar bottlenecks with a shortage in staff, workstyle reforms and lack of DX. It’s gotten tough for warehouse workers because the transport side of the biz had to alleviate their burden somehow. This means it’s not feasible to pass the burden to the warehouses further. So as you can imagine costs for logistics are increasing across the board, and this doesn’t just apply to the truck drivers.

All in all, it all sounds pretty bad but I don’t think it has to be. In some respects, these are the very opportunities and a turning point for some to really change the way things work. Labor as a % of total cost for trucking is already 60%, and margins are so slim that there’s just not that much room to increase this in a meaningful way. The time cap means the moment has come for the industry to really rethink what the options are. Here are a few secondary effects I think will happen going forward. (Or already is!)

Some of the things we’re starting to see:

Consolidation:

One of the main issues is that many of these truck drivers are small businesses spread across Japan, this might not be unique to Japan but this results in less efficient operations and intense price competition. The bigger players have denser logistics networks, efficient and automated infrastructure, deeper pockets, and an edge on hiring. This in itself could present interesting event-driven opportunities. There have been several parent-child listed logistics companies taken over by larger operations. We are starting to see an industry shake-up and this could be a continued trend going forward. It seems there is definitely some appetite for M&A. For the initial round of bidding for Alps logistics, there were 15 bidders.

Some recent examples:

Logisteed (KKR owned) take over bid of Alps Logistics

Seino Hd acquisition of Mitsubishi Electric Logistics

Maruwa’s hostile take over attempt of C&F Logistics (Later acquired by SG hd)

Note that two of them acquired are subsidiaries of larger orgs and are non-core operations of its parents.

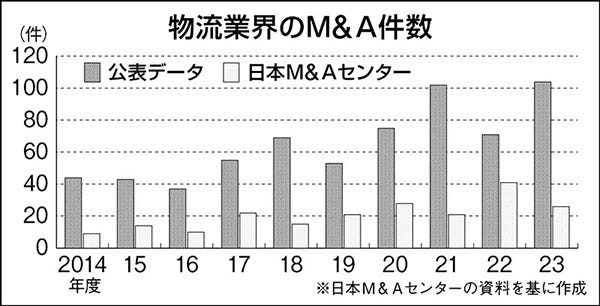

M&A activity is at an all-time high:

Specifiically for AZ-Com Maruwa $9090.JP, which is most known as one of the main 3PLs for Amazon Japan, the founder Wasami-san expressed the importance of combining the resources of several players and investing in digital/more efficient operations together. The founder either directly or through AZ-COM owns shares in other listed peers and it seems likely he considers them as potential takeover targets. Most recently they attempted a hostile takeover of C&F Logistics and ultimately lost to SG Holdings. This plays both into the 2024 problem but in some cases also the Governance Improvements of Corporate Japan (i.e. getting rid of parent-child listings).

In that context if you look at what Wasami-san personally owns + what Maruwa owns they start to look like potentially interesting future take-over targets:

SBS Holdings ($2384.JP)

Hamakyorex ($9037.JP)

PHYZ Hdg ($9325.JP) [Disclosure: I have a small stake]

Kanda ($9059.JP)

e-LogiT ($9327.JP)

Kantsu ($9326.JP)

Kamigumi ($9364.JP)

Trancom ($9058.JP)

Though I note that M&A might not be feasible at all scales. Theres a reason why the # of M&A transactions per 10k companies (the red line) is alot lower than the average across all sectors. As somewhat of a commoditized service there has been little incentive for logistics companies to ‘tuck-in’ small scale operations. They would rather form partnerships/agreements and in effect make these service as a variable cost rather than a fixed cost by acquiring them. Therefore a consolidation among the larger player doesn’t make it easier on the smaller players. It may even make it more difficult if only the larger players consolidate since they’ll have more say in things. So, from what I think, it will start to become increasingly relevant if industry wide trucking rates go up to a point that the economics then starts to make sense.

Partnerships

A close alternative to consolidating operations of multiple players another way in which this might be realised will be through partnerships or so called ‘alliances’ in which the operators combine their capacity in a similar vein to how airlines operate nowadays. The interest levels seem to be high here and may be a viable option for those that do not want to cede control. However, if the partnerships involves one large company and one very small one - it’ll end up with a similar result of the smaller player getting bullied into agreeing on poor rates.

Businesses closing down:

The unfortunate consequence is that not all of it will be saved, some trucking businesses will no longer be able to afford the increase costs and/or opportunity loss and this is likely to lead to bankruptcies. Teikoku databank reported a record high number in bankruptcies in the logistics sector this year. This type of churn might not necessarily be bad, as drivers then can take this opportunity to find a job at a larger firm with better pay/working conditions.

DX/ Operational Efficiency:

Most importantly we’re starting to see more and more need to DX across the supply chain, be it the use of digital order platforms, warehouse automation and even autonomous robots. The other opportunity that could materialize is effectively overcoming some of the things that are causing the current inefficiencies. The example of use of standardized pallets + Forklifts could become a bigger business in the future.

Innovate or die:

It’s quite remarkable how people, society can adapt to such changes, these are still early days but its exciting to see people use their ingenuity to solve this very real problem:

The one I thought was really creativewas using passenger bullet trains to carry cargo. (Although I have no idea how much improvements this would bring)

Trucking innovation:

This seems to be the more scalable solution. Trucking itself is also evolving. Though not new the government is more open to ‘double trucking’ i.e. a single truck carrying two cargo loads. Recently furniture retailer Nitori $9843, announced its partnership with Fukuyama transport for such solution.

Similarly the country is now experimenting with self driving truck convoys.

To aid this, Japan has announced a potential dedicated expressway for unmanned trucks to drive between Nagoya and Tokyo one of the busiests logistical nodes. This is still at the pilot stage but the benefits are clear. It requires less drivers, reduces accidents, reduce transport tie (i.e. no traffic jams) and no jams mean its also more environmentally friendly.

This year the ministry of land, transport and Infrastructure (METI) also announced its interest in creating a similar highway connecting Osaka and Tokyo. This is projected to reduce 35,000 trucks on the road per day.

As much as these all sound great it will likely take time, the above is expected to be running in ten years (so lets add a couple more years to that…) there are also cost considerations that need to be taken into account to see if this really makes sense financially. Which is unclear because im too lazy to look it up.

In summary

The ‘2024 problem’ is just a catchy name and the issue is far more complex than what one might imagine. So even though it sounds like this is only a concern for 2024, this is an issue that Japan will be working to solve for many, many years.

As I said earlier, the issue itself could present interesting opportunities in the capital markets but also for entrepreneurs who may have a business idea to solve this problem. In particular what catches my eye was the opportunity in Digitalisation and consolidation. These are both applicable to other industries as well but is dire in this industry and as such there is some urgency. There are still several listed mid-sized logistics companies on the market and one way to play this would be to figure out which one could become a potential takeover target. On the digital side, I like this as a play because it’s less reliant on human capacity and could potentially see the most upside in terms of efficiency gains.

There are many other causes of inefficiencies than the ones I listed and these are worth thinking about as an opportunity too if this interests you.

In part 2, I’ll be sharing an idea I think that could ride this trend. Thanks for reading!

Disclosure: The author currently owns shares in the company as of 15 September 2024. The security could be sold at any point in time without prior notice.

Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only. Nothing should be considered as investment advice or as a guarantee of profit. It may include some errors, please make sure to do your due diligence. The opinions expressed are those of the author and are subject to change without notice.