Hikari Tsushin Part 2: The investor

How their investment portfolio achieved a 17% IRR and what we can learn from them

Disclaimer: The content on this website is for informational and educational purposes only and is not created to meet your personal financial situation. Nothing should be considered as investment advice or as a guarantee of profit. You are advised to consult with your financial advisors to discuss your investment options and whether it would be a suitable investment for your personal needs. The information used in this publication is from sources that are believed to be reliable but the accuracy cannot be guaranteed. It may include some errors, please make sure to do your due diligence. The opinions expressed are those of the author and the author only. These opinions are subject to change without prior notice.

Make sure to scroll all the way down for bonus content :)

Reading time: 25 mins

Just in time for the Berkshire weekend!

Today, we’ll be discussing Hikari Tsushin, the Investor. I think this gets to the core of how Hikari thinks and operates today - and will continue to as long as they can keep the culture in place. Now, strictly speaking, Hikari thinks like investors in the operating business too! In fact, they probably see the investment business as an ‘operating’ business! So much so that at some point in the early 2000s, they even planned to change their accounting method so that they could put their investment gains in operating profits rather than their XO income/losses. (they didn’t go through with it in the end)

Anyways, we’re mainly going to talk about their portfolio of public investments. This might have a wider appeal, given that whether you’re invested in Hikari or not, they may own some of the companies that you do- and you may want to know what that means! I sure did, given they own so much of the stuff I do. They’ve also proven to be great investors, so hopefully, we can take a page out of their playbook on how to invest successfully in Japan.

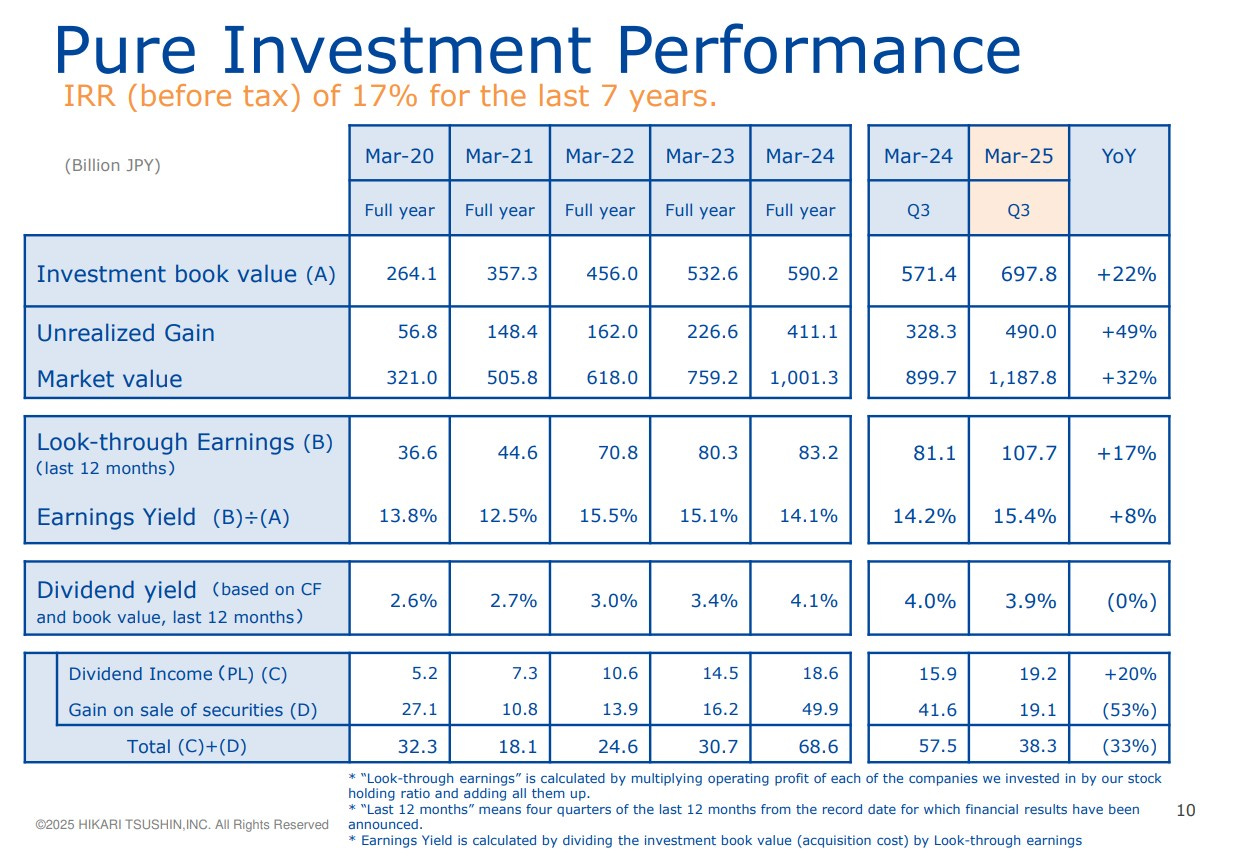

As we go through it, you’ll see a glimpse of why Hikari gets compared to Berkshire so often. It’s no accident. They have the numbers to back it. Their investment portfolio, consisting of hundreds of companies, has done a reported pre-tax IRR of 17% over the last 7 years. This isn’t just impressive as a publicly listed company; it’s just impressive across any investor cohort. period. To put this in context, TOPIX has returned at a 7% CAGR in the same period. Notice that they’ve managed to do this with a portfolio of hundreds of stocks, which implies a ridiculous hit rate.

Hikari in both the investment and operating business focuses on asymmetry, and is able to structure their decisions in a way that minimizes severity of the downside risk.

Like Berkshire, Hikari thinks of stocks as owning a portion of a company and even reports ‘look-through’ earnings from its portfolio companies. They’re astute allocators of capital and a true student of the game.

And I say student because they also seem to be a learning machine. A comment that stuck with me is how the CEO said they studied (other than Berkshire), companies like Danaher, Constellation Software, 3G Capital, and Brookfield Asset Management. The last one, especially on the use of leverage. From my understanding, they even have a team that studies some of the great business cases and creates reports to be read by the rest of the organisation - this even includes companies like Alphabet and Visa. They have the hunger to learn from the best of the best.

For me, writing this was worthwhile to understand how Hikari synthesized learnings from these greats and how they’ve tried to apply them in the Japanese market - and if we should be paying attention to their public investments at all.

We’ll go through:

Hikari’s Investment Strategy: what they invest in, how they find ideas, how they trade, and when they sell)

Synergies with their operating business

What it means to have Hikari as a fellow shareholder

What companies think when Hikari invests in them

Valuation of Hikari as a stock

Potential Risks and Caveats

Gathering information has not been as easy on this side of things but I’ve tried to patch together info provided by the company as well as feedback I got from other investors/companies on Hikari. So please note that this may not be accurate. Nothing can ever be 100% accurate, of course, but in the sense that this has been harder to verify, so it may be more subject to (my) misinterpretation.

Hikari’s Investment Strategy

If I had to describe Hikari’s investment principles in a single word, it would be simplicity. It’s remarkable how simple they’ve kept it, though not really surprising considering the founder’s essentialist approach to business. Despite being a ¥1.7 trn market cap enterprise, there seems to be no complicated models or any of that. Yes, they’re value investors, but as the CEO said: Hikari invests in things you can tell are cheap at first sight.

I’ll repeat, They invest in businesses that are obviously cheap.

This is especially interesting because their equity portfolio is worth ¥1.2tn run by a team of just 4 people! (Although in their recent Q&A, they claim roughly 10 people… I’m assuming this includes the back office.) Sure, some lean and mean hedge funds could do this, but consider this: The head + 3 others are just internal hires from Hikari - no professional money managers. You can already tell by the career history of the head of investments, Takahashi-san, who was previously director and General manager of the financial planning department. The portfolio has continued to do handsomely since he took over.

At least from what I’m told, their work doesn’t sound like that of a buyside analyst, like, at all. They have a quantitative database of companies, and they are continuously looking at this ever-evolving list based on value and quality metrics. From there, they determine what to buy, which may involve talking to the company but overall sounds like a relatively quick process. Note that Hikari is a highly decentralised organisation, and this is no different for their Investment Arm; this small team more or less gets full autonomy on their decisions. No investment committees, and each team member is said to have a lot of freedom in executing trades.

The portfolio of investments consists mostly of Japanese equity, representing more than 80%. The remaining overseas holdings mainly consist of Berkshire Hathaway and some Alphabet.

For them, they see the Japanese equity market as an extremely asymmetric opportunity set. Hence why if they could, they’d borrow debt at an extremely cheap rate (say 1.5% in Japan) and put way more money in these undervalued shares. In practice, though, banks are hesitant to lend them money that cheaply at the scale they want. Lol.

So, when it comes to the sources of financing for their investments, the reality is that at every annual shareholder meeting, the board allocates a budget from its operating cash flow in addition to reinvesting dividends and capital gains (from the equity portfolio) back into the investment arm.

Specifically, a strict rule they have at the firm is to make sure to have enough cash to cover all interest-bearing liabilities maturing in the next 3 years. Anything above this is deemed excess cash, which can be allocated to the investment business. If Hikari cannot find good investments, they will return it to shareholders instead.

In terms of the types of businesses they look for, Market Cap doesn’t matter to Hikari. Unlike most other asset managers, Hikari is willing to invest in a pocket of the market that most institutions aren’t willing to or simply can’t. Namely, companies with very small market caps and/or limited liquidity.

In line with their operating biz, Hikari loves businesses that have some form of recurring revenue; it doesn’t have to be a subscription business per se, but anything that is recurring in nature. This means, among others, things like maintenance service-driven businesses.

Really, what they ultimately want is a form of resilience in these businesses. They also look for 2 other components closely when they invest, which are: a strong balance sheet and those that have been consistently profitable in the past.

That’s it!

The other consideration, of course, is valuation.

How do they think about valuation?

The fascinating part is that while the company reports on IRR for their equity portfolio, this is not their main KPI. They’re not even focused on a particular IRR hurdle per se. It’s just the result of their investment process. A metric they do look closely is the company’s earnings yield (EY). Which they define as:

EY = Operating profit per share ÷Share Price (at Cost)